The Evolution of the Army Medical Corps

The history of military medicine in the United States during the 18th and 19th centuries is essentially the history of the Army Medical Corps. There is no surprise that the Army Medical Corps played a significant role in advances in battlefield medicine. However, many people do not appreciate that the Army Medical Corps also played a significant role in the treatment of infectious diseases and improvements in general sanitation. For example, one of the first public health inoculation efforts was ordered by General George Washington in the Continental Army to protect troops against smallpox. Walter Reed led an Army Medical Corps team that proved that the transmission of yellow fever was by mosquitoes. The Army Medical Corps developed the first effective typhoid vaccine during the Spanish American War and in World War II the Army Medical Corps led research to develop anti-malarial drugs.

Revolutionary War and the Founding of the Army Medical Corps

The formal beginnings of military medical organization in the United States trace back to 1775, with the establishment of a Medical Department for the Continental Army. On July 27, 1775, the Continental Congress created the Army Medical Service to care for wounded soldiers. Dr. Benjamin Church was appointed as the first “Director General and Chief Physician” of the Medical Service, equivalent to today’s Surgeon General. However, Church’s tenure was brief and marred by scandal: he was proved to be a British spy, passing secrets to the enemy.

Church’s arrest in 1775 created a leadership vacuum, and the fledgling medical service had to reorganize quickly under Dr. John Morgan, who became the second Director General. Morgan sought to professionalize the medical corps, emphasizing proper record-keeping and standards of care. However, the Revolutionary War medical system struggled with limited resources, inadequate supplies, poor funding and an overworked staff. The lack of an effective supply chain for medicine, bandages, and surgical instruments was a significant issue throughout the conflict.

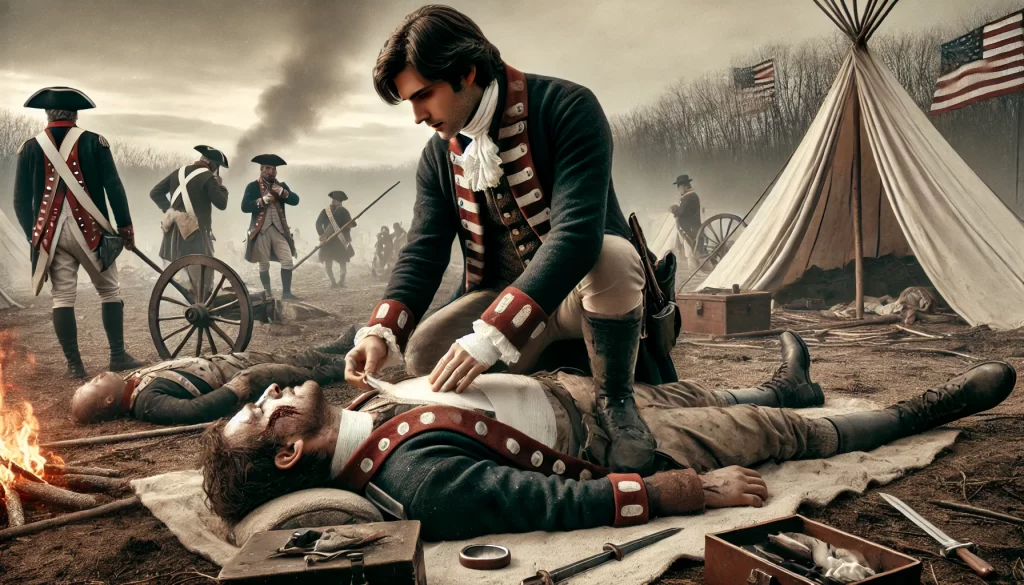

Early Challenges in Battlefield Medicine

During the Revolutionary War, military medical practices were rudimentary. Medical knowledge and understanding of disease processes had advanced little since the days of ancient Greece. Medical training was inconsistent and was principally by the apprentice method. In 1775 there were only two small medical schools in all of the 13 colonies. One of those closed with the onset of the revolution.

Field surgeons primarily treated gunshot wounds, fractures, and infections. Most treatments were painful and often involved amputation, as this was one of the few ways to prevent infections from spreading in an era without antibiotics. Battlefield medicine was further hampered by the fact that surgeons often had to work without proper sanitation or anesthesia.

One of the most significant health challenges faced by the Continental Army was disease, including smallpox, typhoid, dysentery, and typhus. In fact, more soldiers died from disease than from combat injuries. Recognizing the threat of smallpox, General George Washington made the controversial but strategic decision in 1777, to inoculate his troops against smallpox, significantly reducing mortality and helping to preserve the fighting force. At Valley Forge almost half of the continental troops were unfit for duty due to scabies infestation and approximately 1700 to 2000 soldiers died of the complications of typhoid and diarrhea.

It’s estimated that there were approximately 25,000 deaths among American soldiers both continental and militia in the American Revolution. An estimated 7000 died from battlefield wounds. An additional 17,000 to 18,000 died from disease and infection. This loss of soldiers to non-combat deaths has been one of the biggest challenges faced by the Army Medical Corps through much of its history.

Post-Revolution: Developing a Medical Framework (1783-1812)

After the Revolutionary War, the United States Army Medical Department went through a period of instability. There were ongoing debates about the structure and necessity of a standing army and medical service in peacetime. However, the need for an organized military medical service became apparent during the War of 1812. The war underscored the importance of medical organization, especially in terms of logistics and transportation of the wounded.

The Army Medical Department grew, and by 1818, the government established the position of Surgeon General. Joseph Lovell became the first to officially hold the title of Surgeon General of the United States Army. Lovell introduced improvements to record-keeping and hospital management and laid the groundwork for future medical advances, though the department remained small and under-resourced.

Advancements in Military Medicine: The Mexican-American War (1846-1848)

The Mexican-American War provided an opportunity for the Army Medical Corps to refine its practices. Field hospitals were more structured, and new surgical techniques were tested. However, disease continued to be a significant challenge, yellow fever and dysentery plagued American troops. The war also underscored the importance of sanitation in camps, though knowledge about disease transmission was still limited.

The aftermath of the Mexican-American War saw the construction of permanent military hospitals and better organization of medical personnel, setting the stage for the much larger and more complex demands of the Civil War.

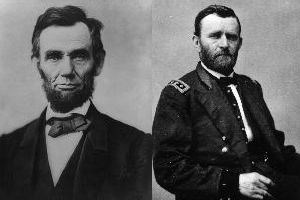

Civil War: The Birth of Modern Battlefield Medicine (1861-1865)

The Civil War represented a turning point in military medicine, with significant advances in both battlefield care and medical logistics. By the start of the war, the Army Medical Corps was better organized than during previous conflicts, though it still faced many challenges. Jonathan Letterman, the Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac, revolutionized battlefield medicine by creating the Letterman System, which included:

- Field Dressing Stations: Located near the front lines to provide immediate care.

- Ambulance System: Trained ambulance drivers transported wounded soldiers from the battlefield to hospitals.

- Field Hospitals and General Hospitals: These provided surgical care and longer-term treatment.

The Civil War saw the introduction of anesthesia (chloroform and ether), which reduced the suffering of wounded soldiers and made more complex surgeries possible. However, infection remained a major problem, as antiseptic techniques were not yet widely practiced and germ theory as a source for disease and infection was poorly understood. Surgeons worked in unsanitary conditions, often reusing instruments without sterilization and frequently doing little more than rinsing the blood off of their hands between patients.

Sanitation and Public Health Measures

One of the most critical lessons of the Civil War was the importance of camp sanitation and disease prevention. Dr. William Hammond, appointed Surgeon General in 1862, emphasized the need for hygiene and camp inspections. Under his leadership, new regulations improved the quality of food and water supplies. Though disease still claimed many lives, these efforts marked the beginning of a more systematic approach to military public health.

Additionally, the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC)was established in 1861. It was a civilian organization that was created to support the union army by promoting sanitary practices and improving medical care for soldiers with the objectives of improving camp sanitation, providing medical supplies, promoting hygiene and preventive care, supporting wounded soldiers and advocating for soldiers welfare.

Hammond also promoted the use of the Army Medical Museum to collect specimens and study diseases, fostering a more scientific approach to military medicine. Though he faced resistance from some military leaders, his reforms laid the foundation for modern military medical practices.

Conclusion

The evolution of the Army Medical Corps from the Revolutionary War to the Civil War reflects a gradual shift from rudimentary care to more organized, systematic medical practices. Early efforts were hindered by leadership issues, such as the betrayal by Benjamin Church, and by the challenges of disease and limited resources. However, over the decades, the Army Medical Department improved its structure, introduced innovations like inoculation and anesthesia, and laid the groundwork for advances in battlefield care. The Civil War, in particular, was pivotal in transforming military medicine, with lessons in logistics, sanitation, and surgical care that would shape the future of military and civilian medical systems.

For further reading, the following sources provide excellent insights:

- Office of Medical History – U.S. Army

- “Gangrene and Glory: Medical Care during the American Civil War” by Frank R. Freemon