We all know a lot about George Washington. Or do we really? And is everything we think we know true? We all know he was the first president, but was he really? He was the commander in chief of the Continental Army, and there is no question about that. He is often called the father of his country. But did you know that he never had any children?

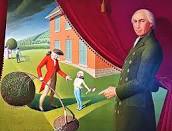

The fanciful tales about George Washington began to circulate while he was still alive. Everyone has heard the story of the chopping down of the cherry tree and how the young George Washington could not tell a lie and that he did it with his little hatchet. Did you know that this story was created for one of the first biographies circulated about George Washington? It was a best seller written by Parson Mason Weems who was more interested in promoting morality than in historical accuracy. We also have the story of how Washington threw a silver dollar across the Potomac. Even though money went further in those days, it is unlikely since the river is about a mile wide at that point.

Presidential Dentures

We’ve all heard how Washington had wooden false teeth. It’s true that he had false teeth; he suffered with dental problems his entire life. But they weren’t made of wood. Washington began to lose his teeth in his early 20s. He had several sets of dentures made throughout his life, including one that incorporated hippopotamus ivory. He also had a set that incorporated human teeth. In the 18th century dentists were known to purchase healthy teeth from living donors who were in need of cash. The dentist would then incorporate these teeth into dentures for their clients. The dentures were cumbersome things that involved metal plates and gold wiring. Can you imagine having these in your mouth?

The First Entrepreneur

George Washington owned and operated one of the largest commercial distilleries in the early United States. Following his presidency, he began work on his distillery at Mount Vernon. He produced mostly rye whiskey, and it was quite profitable. So, not only was Washington first in war and first in peace but he was first in cocktails as well. (That makes him even more of a hero to me!) Margie and I visited Washington’s distillery as recreated at Mount Vernon. I even bought a bottle of his Mount Vernon whiskey that you can see below on my bookcase.

I haven’t yet tried it. The distiller told me it was considered to be very smooth for its day. When I asked him what we would consider it in our day, he said “Pretty rough.” Perhaps some year, on the anniversary of the Battle of Brooklyn Heights, I’ll use it to make a Mount Vernon Manhattan (or not).

Even though Washington owned a major distillery, rye whiskey was not his favorite drink. When at dinner or sitting around the fire with friends he enjoyed a glass of Madeira. It is a fortified wine made on the Portuguese island of Madeira. Washington began ordering Madeira from his London agents in 1759 and continued ordering throughout his life. He usually ordered wine in “pipes” of 150 gallons. He seldom traveled without a large supply of Madeira.

We’ve all been taught to think of George Washington as a planter. But now we know he was distiller as well. Will it surprise you to learn that he was also a commercial fisherman?

When tobacco prices started to fall, Washington looked for ways to diversify his income. He had almost 10 miles of shoreline on the Potomac River. He bought boats and nets and set his enslaved workers to the task of catching shad, herring, perch, and sturgeon. The fish were cleaned, packed in salt, and sold all over the colonies and even shipped to Europe. He went so far as to buy a sailing schooner that he used to ship his fish to such places as Portugal and Jamaica.

A Mountaineer?

Would you believe that George Washington was once a major landowner in what is now West Virginia? Washington received major land grants for his service in the French and Indian war and he also purchased grants from others who were not interested in developing their wilderness land. He owned land at the mouth of the Kanawha River in the area that is now Point Pleasant, West Virginia. He also owned land along the Kanawha River from the mouth of Coal River up to the area that now includes Charleston. So, we can honestly say George Washington was a West Virginian.

The Traveler?

George Washington only made one trip out of what would become the United States. He had been largely raised by his older half-brother Lawrence after his father died. Lawrence had been suffering from tuberculosis and was advised to spend the winter in the tropics. Nineteen-year-old George agreed to go with him on a trip to Barbados. Two important things happened while he was there. He had the opportunity to meet British Army officers and study fortifications and learn about British military armaments and drill. This was the beginning of his lifelong love of all things military.

But perhaps the most important and least well-known portion of this trip was that Washington contracted and recovered from smallpox, leaving him with lifelong immunity. Smallpox had ravaged the colonies for several years and was devastating many units of the Continental Army. Imagine the fate of the revolution had Washington died of smallpox in 1777.

As a result of the epidemic, he issued one of the first public health orders from the American government. He ordered that all recruits arriving in Philadelphia for the Continental Army be inoculated against smallpox. This practice was soon spread across all colonies and even veteran soldiers who had not yet had smallpox were inoculated.

There are many more fascinating things about George Washington, and I will include them in a future post entitled Even More Things You May Not Have Known About George Washington.

The First Question and Final Answer

In case you think I’ve forgotten my question about the first president, Washington was the first president, under the constitution. However, prior to the adoption of the Constitution, while under the Articles of Confederation there were eight men who held the title of President of the Congress and whom some historians consider to be Presidents of the United States. But, unless you’re a true history nerd, you’ve never heard of John Hanson, first president under the Articles of Confederation. It’s The Grumpy Doc’s opinion that his lack of accomplishments earned him his well deserved obscurity.

For even more interesting facts about Washington, see the website www.MountVernon.org.

What Would George Washington and Thomas Jefferson Think About Our Current Political Climate?

By John Turley

On October 16, 2024

In Commentary, History, Politics

In considering what George Washington and Thomas Jefferson might think of today’s political situation, it’s tempting to view their perspectives through the lens of nostalgia, believing that the founders had an idealistic vision that, if followed, would have prevented many modern problems. It’s impossible of course to know what they may have thought about our current environment. Certainly, such things as a 24-hour news cycle on cable television and social media would have been beyond their comprehension. While both men lived in a vastly different era, their writings and philosophies give us a sense of how they might respond to the polarization and tensions we witness today.

George Washington: A Warning Against Partisanship

George Washington was deeply concerned about the rise of factions in the United States. (Political parties as such were unknown at the beginning of our republic.) In his famous Farewell Address in 1796, he warned that factions could lead to division and weaken the unity of the country. Washington was worried that faction (party) loyalty would surpass loyalty to the nation, creating conflict between groups and impairing the ability of government to function for the common good. He feared that excessive partisanship would “distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration,” leaving the nation vulnerable to foreign influence and internal discord.

If Washington could observe today’s political environment, he likely would be saddened by the partisanship which dominates political discourse. The gridlock, belligerent rhetoric, and divisiveness we experience today demonstrate the appropriateness of his concern. Washington would likely advocate for a return to greater civility, urging Americans to focus on the common good and to set aside factionalism for the sake of national unity. While political parties have become integral to our system, Washington would likely still press for cooperation, mutual respect, and compromise among all groups.

Thomas Jefferson: Liberty, Democracy, and the People’s Role

Thomas Jefferson, while more supportive of political parties than Washington, had his own complex views about governance. Jefferson believed in the power of the people to govern themselves and was a passionate advocate for liberty, democracy, and decentralization. He distrusted concentrated power, whether in government, or economic institutions, and feared that it could lead to tyranny. Jefferson was famously a champion of agrarianism and believed that widespread participation in the democratic process was the best defense against corruption and the loss of liberty.

Jefferson, while a proponent of states’ rights and individual liberties, might view polarization as a threat to democratic ideals if it stifles dialogue and compromise. He believed in the potential for free men to govern wisely, but would caution against the erosion of civil discourse that might follow the rise of extreme factionalism

Faced with the highly charged political debates of today, Jefferson would likely express concern over the increasing centralization of power in government, banks, and large corporations. He would, without doubt, be troubled by the outsized influence of money in politics.

Jefferson was also a firm believer in education as a cornerstone of democracy; he would stress the importance of an informed electorate, particularly in an age where misinformation can spread rapidly.

However, Jefferson was no stranger to political conflict, having played a central role in the fiercely partisan battles of his time. He understood the value of vigorous debate but would probably urge that such debate remain focused on the core democratic principles of liberty, justice, and equality rather than devolving into personal attacks.

Media and Civil Discourse

Of course, it is impossible to know what Washington and Jefferson would think about the current role of media, particularly social media which would be beyond anything in their experience. Washington felt strongly aggrieved by the attacks upon him in the newspapers of the time. He felt unfair attacks would undermine national unity. Jefferson, on the other hand, was a strong proponent of freedom of the press. He was also very adept at the use of newspapers to accomplish political means.

However, it is likely that both would caution against the dangers of misinformation and partisan bias to distort public perception. Most likely both would emphasize the need for a responsible press that distinguishes between fact and opinion and supports a healthy democracy. Both would be opposed to using false or misleading statements to influence the public.

Unity and Civic Responsibility

Despite their differences, both Washington and Jefferson would likely agree on one thing: the importance of unity and civic responsibility. They envisioned a country where citizens were deeply involved in a participatory government, contributing not just with votes but with informed, constructive dialogue. Washington would call for a spirit of national unity above party lines, while Jefferson would insist that the preservation of liberty relies on active and informed participation from the public.

Both founders would encourage a healthier, more cooperative political environment, one where differences are respected and not allowed to fracture the country. They would likely see today’s polarization as a threat to the very ideals they fought to establish, and both would urge Americans to remember their shared values.

Conclusion

In short, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, while men of their own time, had insights that are still relevant today. Neither man could have predicted the exact nature of modern politics, but their wisdom offers enduring guidance: political disagreements must not undermine the unity, liberty, and civic responsibility that are the foundation of the American experiment. We owe it to them not to lose the promise of the American Revolution.