A Brief History of the U.S. Navy Medical Corps

The U.S. Navy Medical Corps has a history that evolves from a humble beginning during the Revolutionary War to its current role as a vital component of modern military medicine. The Medical Corps ensures the health and well-being of sailors, Marines, and their families, while contributing to public health and advancements in medical science.

Origins in the Revolutionary War

The roots of Navy medicine trace back to the Revolutionary War, when medical care aboard ships was primitive at best. Shipboard surgeons, often lacking formal medical training, treated injuries and disease with the limited tools and knowledge available to them. In the early days of the U.S. Navy, physicians served without formal commissions, often receiving temporary appointments for specific cruises. Their primary tasks included amputations, treating infections, and caring for diseases like scurvy and dysentery.

In 1798, Congress formally established the Department of the Navy, creating the foundation for organized medical care within the naval service. Surgeon Edward Cutbush published the first American text on naval medicine in 1808. The Naval Hospital Act of 1811 marked another milestone, authorizing the construction of naval hospitals to support the growing fleet.

Establishment of the Navy Medical Corps (1871)

The U.S. Navy Medical Corps was officially established on March 3, 1871, by an act of Congress. This legislation created a formal medical staff to support the Navy, setting standards for the recruiting and training naval physicians. These physicians were initially known as “Surgeons” and “Assistant Surgeons,” tasked with providing care on ships and at naval hospitals. The act granted Navy physicians rank relative to their line counterparts, acknowledged their role as a staff corps, and established the title of “Surgeon General” for the Navy’s senior medical officer.

During this period, the Navy Medical Corps began to expand its scope. It embraced emerging medical technologies and scientific discoveries, setting the stage for its later contributions to public health and medical innovation.

The Navy Hospital Corps

The U.S. Navy Hospital Corps was established on June 17, 1898. Its creation was prompted by the increased medical needs during the Spanish-American War. Since then, the enlisted corpsmen have served in every conflict involving the United States, providing critical medical care on battlefields, aboard ships, and in hospitals worldwide.

Corpsmen are trained to perform a wide range of medical tasks, including emergency battlefield triage and treatment, surgery assistance, and disease prevention. They are often embedded directly with Marine Corps units, making them indispensable on the battlefield.

The Hospital Corps is the most decorated group in the U.S. Navy. To date, its members have earned numerous high-level awards for valor, including: 22 Medals of Honor, 182 Navy Crosses, 946 Silver Stars, and 1,582 Bronze Stars.

World Wars and the Expansion of Military Medicine

Both World War I and World War II were transformative for the Navy Medical Corps. During World War I, Navy medical personnel treated injuries and illnesses both aboard ships and in field hospitals. Their efforts were instrumental in managing wartime epidemics, including the devastating 1918 influenza pandemic.

World War II brought further advancements. The Navy Medical Corps played a pivotal role in addressing the challenges of warfare in diverse climates, including tropical diseases in the Pacific Theater. It also pioneered methods for treating trauma, burns, and psychiatric conditions.

Cold War Era and Modernization

The Cold War era marked a time of significant innovation for the Navy Medical Corps. The establishment of the Navy Medical Research Institutes advanced studies in areas such as tropical medicine, submarine medicine, and aerospace medicine. These efforts supported the Navy’s global missions and contributed to broader medical advancements.

In the latter half of the 20th century, Navy medical personnel became key players in humanitarian missions, responding to natural disasters and providing aid in conflict zones. Their expertise in public health, infectious disease control, and trauma care enhanced the Navy’s ability to spread goodwill worldwide.

Modern Contributions and Future Challenges

Today, the Navy Medical Corps supports both military readiness and global health. Its personnel provide care on ships, submarines, aircraft carriers, and for Marine Corps forces, and at shore-based facilities. They also participate in humanitarian missions and disaster response, reflecting the Navy’s commitment to a broader vision of security and well-being.

In recent years, Navy medicine has faced challenges such as the COVID-19 pandemic, addressing mental health issues among service members, and adapting to emerging threats like climate change and cyber warfare defense. These challenges underscore the evolving role of the Navy Medical Corps in a complex world.

From its early days of rudimentary care to its modern role in global health and innovation, the U.S. Navy Medical Corps has been a cornerstone of military medicine. Its contributions extend beyond the battlefield, shaping public health, medical research, and humanitarian efforts worldwide.

As the Navy Medical Corps continues to adapt to new challenges, it remains a testament to the enduring value of medical service in the defense of the nation and the promotion of global health.

Travels of a West Virginia Boy Part I, Hong Kong

By John Turley

On February 20, 2023

In Commentary, Travel

The first time I left the United States I was 21 years old and on my way to Vietnam. In one of those little ironies of life, I would visit Hong Kong three times before I ever made it to New York City. Growing up in West Virginia, my family thought a trip to Myrtle Beach was the height of travel. It’s still the destination of choice for many West Virginians and I still love the South Carolina low country and fried sea food.

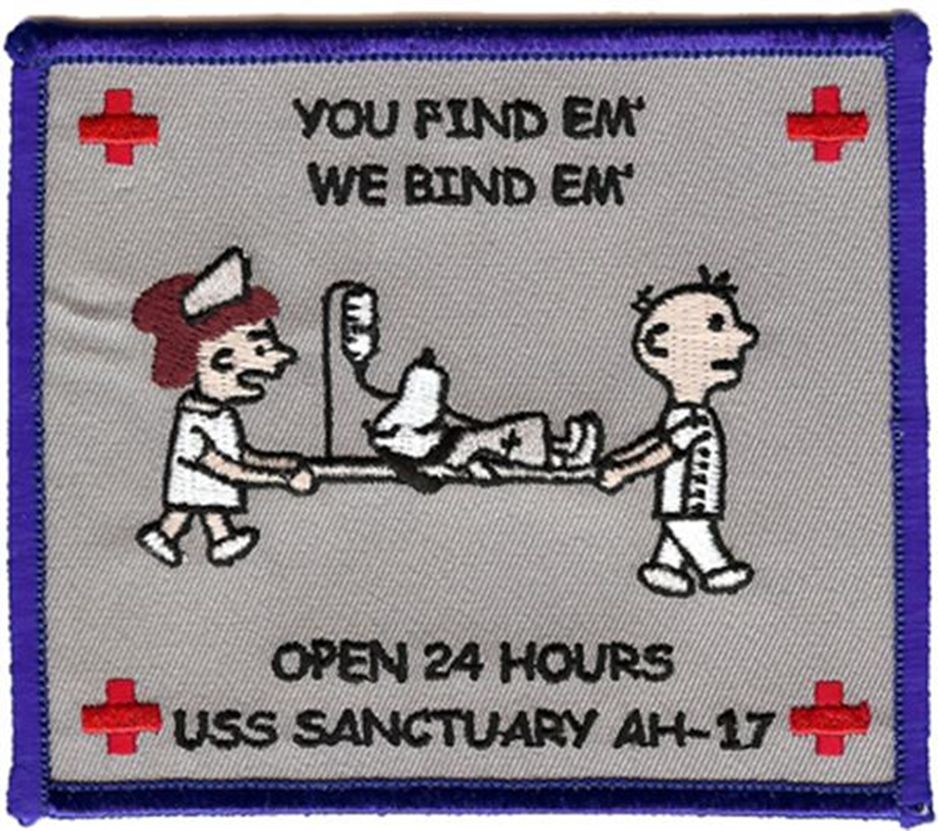

My first trip to Hong Kong was in the spring of 1970. I was serving on the USS Sanctuary in the coastal waters of Vietnam. I had my R&R (Rest & Recreation) trip planned to Australia later in the summer. However, I received orders ending my tour early because I was to report for a training school in San Diego in early June. This meant if I wanted to go on R&R it would have to be soon. The only R&R destination available in my time frame was Hong Kong. I knew next to nothing about Hong Kong. The closest I had come to Chinese culture was chop suey at the New China Restaurant in Charleston.

R&R was basically a five-day vacation that the military gave you when you were serving in the Vietnam area. It was something you looked forward to for the first part of your tour and then you would dream about it for the remainder.

Even flying into Hong Kong was an exciting experience. The old Hong Kong airport was almost in the middle of the city. The flight path carried you down between the buildings. I remember looking out the window of the plane and into the window of an apartment building. There didn’t seem to be enough room for the wings in between the buildings, but somehow the plane landed without incident. That initial look out the window may have been one of the most surprising things that I have experienced.

When we first arrived, we were given the typical military orientation lecture that included warnings about venereal disease with a large map that showed us the areas of Hong Kong we should avoid. Of course, for many of us that meant those were the areas we were going to head to first. They also gave us a list of hotels we could afford without spending all our R&R money.

Hong Kong was like nothing I had ever seen before. I spent the first day wandering around the crowded streets watching the people and trying to sort out the multitude of sights and smells. There was an odd combination of delicious, exotic and downright strange. Street food was everywhere and so were street vendors. The first day I was determined to sample as many different foods as possible. They varied from delicious to inedible. I’m sure that was just me, because the Chinese people seemed to most enjoy the food I couldn’t eat.

I also looked in a lot of shops trying to decide what I should buy. The shop people were friendly and spent a long time answering my often rambling questions. I had been advised to be very careful about negotiating prices. A Chief Petty Officer who was familiar with Hong Kong (his wife was Chinese) told us, “The Chinese people are basically honest. They won’t steal from you, but if you’re a bad negotiator, they are glad to let you pay three times what it’s worth.” In Hong Kong you even bargained over the price of a pack of gum, a skill I never really developed.

I eventually decided I would have a suit made because I had never had a tailor-made suit. I also had some shoes made. I’m sure that because of my poor negotiating skills I paid more than I needed to, but I was happy with the price and that was all that mattered to me. I thought I was pretty fashionable, but looking back I probably could have done better in my selection of material. The shiny shark skin material that looked so cool on Frank Sinatra didn’t do anything for me. The shoes were nice though. I wore a size 14 narrow, and it was nice to have a pair that actually fit.

The second night in Hong Kong as I was leaving the hotel, I ran into an Australian sailor who had been to there many times before. He said he’d show me the “real action” in Hong Kong. As we walked along, he turned down a narrow and dark side street and then into a basement level bar that had a big neon sign that said “Club Red Lips” with a big pair of neon lips underneath it. The place was dark and crowded with a lot of Australian sailors and Chinese women. It smelled of stale beer, cigarettes and sweat. After two beers my new friend turned to me and suggested getting out of there and going someplace where there would be some better action.

We started down the street and as he was ready to turn in to an even darker and narrower alley, I suddenly remembered I had someplace else to be. The “real action” was starting to seem a little too risky to me.

I begged off and headed back to a better lit part of town to have dinner and drinks with other American sailors. I suppose it was something he was accustomed to, but it was a little too much for a West Virginia boy to deal with. It turned out I was not as rowdy as I thought.

Most of the rest of my R&R was spent doing the typical tourist things and riding tourist buses. I didn’t venture down any more dark and narrow side streets. But I really did have a good time.

My next trip to Hong Kong was in May of 1975. By this time, I was in the Marine Corps and was an infantry officer. I was part of a Marine Amphibious Force that was embarked on Navy ships. We had recently completed support of the evacuations of Saigon and Phnom Penh and the recovery of the merchant ship SS Mayaguez. Our ships anchored in the harbor in Hong Kong for liberty call for the sailors and the embarked Marines.

Since I was one of the few officers in our battalion who had been to Hong Kong, I was tasked with briefing the troops on the things they could do there. I spent quite a while going through the ship’s library to find a few things about Hong Kong and then doing my best to remember some of the things that I had done during my previous visit. Of course, there was no internet to check.

I was happy that I had come up with a quite detailed list of sights to see and places to go. I gave my briefing. I told them where they could catch buses and where they could catch the ferry and where there were good places to shop and where there were good places to eat. When I finished, I ask for questions and the first question was, “Is it true that there’s a Kentucky Fried Chicken in Hong Kong?” Yes, it was true.

While I didn’t have any fried chicken in Hong Kong my friend Walt and I decided to be a little adventurous. We went to a “non-tourist” restaurant. Walt ordered pigeon, thinking it would probably be Cornish Game Hen and I ordered beef with bitter melon thinking how bitter can it really be, after all it is melon. Well, Walt’s pigeon was pigeon, and it came complete with head, beak, eyes, and feet. My melon was so bitter I couldn’t eat any of it.

Our stay in Hong Kong lasted four days and then we were back onboard ship to return to our home base in Okinawa. I knew I would be returning to Hong Kong in a few months when Margie joined me for Christmas leave.