I reported on board the USS Sanctuary in September of 1969 and went to the personnel office for my assignment. This won’t surprise anyone who was ever in the Navy, but they seemed to have no idea that I was coming. After conferring among themselves, they came back and told me that I would be senior corpsman in sterile surgical supply.

Sterile surgical supply was where we prepared and maintained all the equipment necessary for conducting surgery as well as the sterile equipment used in the clinics and wards. The Sanctuary had several surgical suites that were busy almost all the time when we were on station in support of combat operations. It was a busy place and went through a lot of equipment.

Life on board a Navy ship is a 24 hour a day, seven day a week job. There are no days off when you’re at sea. Fortunately, as a member of the hospital crew, I was what they called a shift worker. Which meant I had a set schedule. Members of the ship’s crew were watch standers. That meant they worked in four hour rotations that changed every 24 hours. We could at least have some type of a routine for awake and sleep time, but for a watch stander the schedule was constantly rotating. As a petty officer and a supervisor, I was exempt from some extracurricular duties such as working on the mess decks and taking part in working parties for regular ship maintenance and supply.

The work was hard and continuous. There was no shortage of casualties in 1969. Our job was to provide direct medical support to our troops in combat. The wounded were flown by helicopter directly from the battlefield to the ship. We got the most severely injured; the ones who couldn’t be effectively treated at a field hospital.

The crew was highly trained and incredibly efficient. From the time a wounded soldier or marine landed on our flight deck it was only minutes until he was in the operating room. The survival rate for the wounded in Vietnam was far greater than it had been in either World War II or Korea. This was largely due to the speed with which casualties were transported to definitive medical care.

We generally didn’t treat civilians, but one day, unbeknownst to us, one of our medevac helicopters was bringing in a pregnant Vietnamese woman. When she was offloaded on the flight deck she was already in labor. They brought her down to the preoperative holding area which was adjacent to our sterile supply room. When there was a heavy influx of casualties, we helped out in the preop area that functioned somewhat like an emergency room.

We were standing there, an anesthesiologist and three corpsmen, trying to figure out how to deliver a baby. Thank goodness the woman took it in her own hands and delivered the baby herself! Of course, that didn’t stop us from congratulating each other about delivering the only baby born on a Navy hospital ship during the Vietnam War. If only all our patients could have turned out so well.

When I remember my time on the Sanctuary, I try not to dwell on the suffering of our patients. Their sacrifices still move me to tears. I prefer to be grateful that I was mostly out of direct combat and to focus the less intense episode that helped us maintain our sanity.

One unexpected benefit of being the senior corpsman in sterile surgical supply was being able to order those supplies. One day while going through the supply catalog I discovered it was possible to order five gallons of pure medical grade grain alcohol. And even better, it required no approval. I also ordered a large five gallon glass beaker. We had wall mounts in our work room where there were glass beakers with soap solution and acetone. We also had an empty wall mount.

The alcohol arrived, along with the five-gallon beaker. I put the alcohol in the beaker and pasted a large poison sign on it. I got green food coloring from the mess decks in return for a promise to share. It’s easy to be generous when you have five gallons. I did have to emphasize that it couldn’t be drunk straight but had to be diluted by fifty percent with fruit juice or soda.

The food coloring gave it an appropriately poisonous appearance. It also gave us the advantage of hiding it in plain sight. I quickly became the most popular corpsman on the ship.

Right after Thanksgiving the CO of the ship issued an announcement that the crew was now authorized to put up Christmas decorations. (I think I’ve mentioned before that sometimes I don’t always think through my wise cracks.) The fact that we were now authorized to have Christmas got me thinking. I made a large sign that said “All enlisted personnel desiring to have a Merry Christmas must report to the ship’s office to obtain a Christmas chit. Personnel having a Merry Christmas without an appropriate chit will be subject to nonjudicial punishment.” A chit was basically the Navy’s version of a permission slip. I thought this was pretty funny. Apparently, the ship’s office did not agree when people started lining up to get their Christmas chits.

This resulted in a stern lecture from our leading chief. It generally consisted of about every third word beginning with the letter F. I was sure I was going to be reassigned, reduced in rank, sent to the brig or something even worse. Surprisingly, after many blistering words, he dismissed me with a wave of the hand. As I was leaving, much relieved, the chief said, “And you can drop off the rest of that grain you got to the chief’s mess .” That depleted my supply and ended my short-lived popularity on the USS Sanctuary.

Right after Christmas, we had the opportunity to have a Bob Hope show on board the ship. Everyone was crammed onto the main deck to watch Bob, a few musicians and some dancers put on about an hour and a half show. I was way in the back as we had all the patients in the front. Bob’s jokes were corny. I’m sure the dancers were pretty (I wasn’t close enough to tell for sure) and the musicians weren’t particularly talented, but a good time was had by all.

Navy ships at sea in a combat zone practice strict blackout at night. Hospital ships don’t. Not only are they painted white, but they are lit up like a cruise ship with large flood lights hanging over the side of the ship to illuminate the red crosses. This illumination led to what quickly became one of our favorite pastimes.

Inshore ocean waters in Southeast Asia are infested with sea snakes and they are attracted to light. One sailor had his parents send him a sling shot and BBs and before long the ship’s rails were lined with sailors firing BBs and watching the snakes rolling in the water. For most of us, these were the only shots we fired in Viet Nam.

Once, while cruising close to the mouth of the Perfume River near Hue City, the ship went dead in the water. The rumor quickly spread among the crew that the NVA had attached a mine to the hull. Everyone rushed on deck to watch as divers went over the side to investigate. Imagine our disappointment when they surfaced dragging a large fishing net that had wrapped around the propeller.

I don’t remember as much about the trip home from Vietnam as I do about the plane ride over. I do remember that as soon as the plane lifted off the ground everyone on board started cheering and applauding and whiskey bottles were passed up and down the aisles. (Perhaps that’s why I don’t remember much about the flight.) Needless to say, it was a very happy trip.

There were other events that I may share at some point, including a misguided trip to Camp Eagle and several port calls to the infamous Olongapo in the Philippines. However, this post has gone on long enough, but I may return later to revisit these memories.

We arrived at Norton Air Force Base, which I now knew was in Ontario, California, not Ontario, Canada. They took us through customs and started searching our bags. I was wondering why, because I couldn’t imagine anything we could possibly be bringing back that would be valuable enough for customs to worry about until I saw them going through bags and pulling out weapons, grenades and even a mortar shell.

This was in the spring of 1970 and the height of the Vietnam War protests. As soon as we cleared customs, they put us in a large auditorium and gave us our welcome home briefing. One of the few things I remember from this is that we were told that if we did not have civilian clothes that we should go to the base exchange buy some and put them on before we got to LAX. Under no circumstances should we go to LAX in uniform because we would be harassed or possibly even assaulted by protesters. This was not quite the welcome home any of us were expecting.

I was on my way to an officer training program and four years in college. I was sure that by the time I graduated and got commissioned the war in Vietnam would be over. But, like many things associated with that war, nothing would ever be certain, and I would see that sad country again.

Anchors Aweigh, Part III

By John Turley

On January 20, 2023

In Commentary, History, Medicine, Travel

When I left my duty station in Key West, the Navy handed me my orders and a check to cover my travel costs. As always, they left it up to me to figure out how to get there. I didn’t worry about that for the first two weeks. I was at home in Charleston, WV, and when I had a week left in my leave, I thought it was time to figure out how to get from Charleston to Norton Air Force Base, where I was supposed to get government transportation to take me to my new duty station, the hospital ship USS Sanctuary that was cruising off the coast of Vietnam.

I asked my father. He had never heard of Norton Air Force Base either and he suggested we contact a friend of his who was a travel agent. So, Dad gave him a call and two days later I went down to pick up the tickets. The agent handed me an airline ticket to Ontario International Airport. While I was trying to explain to him that I wasn’t going to Canada, that I was going to take my orders to Vietnam, he laughed and told me that Ontario was actually in California. It was the closest commercial airport to Norton Air Force Base.

While the Navy had given me money for transportation, it would only cover coach. In those days a coach seat was about the size a first-class seat is today. That flight took me to California where I got a bus to the Air Force base for the government chartered flight to Vietnam.

It was a long trip from California to Da Nang. We stopped in Hawaii to refuel. Unfortunately for us, they wouldn’t let us out of the airport. We were on that airliner long enough that they fed us three times, once on the way to Hawaii and twice between Hawaii and Da Nang. All three meals consisted of baked chicken, peas and carrots, and mashed potatoes. It wasn’t so bad for lunch and dinner but baked chicken for breakfast just wasn’t something I was up for. In typical government style we had three meals supplied by the lowest bidder.

I arrived in Da Nang to discover that the Sanctuary only came in port about every 6 to 8 weeks to resupply and wasn’t due back for three weeks. I got assigned to the transient barracks, where the Navy puts people awaiting further assignment. Sometimes at morning muster (roll call) they gave us jobs such as unloading trucks or doing basic lawn maintenance. Most of the time we were on our own to entertain ourselves.

The transient barracks was in Camp Tien Sha, a Sea Bee run support base. The most popular place on the base for enlisted men was the movie theater. It was open 24 hours a day and was free of charge. You could bring your own beer and they even allowed smoking in the theater. (Everyone smoked in the 60s.) They only had four movies which they ran in continuous rotation. But most importantly, it was the only place on base that an enlisted sailor could go that was air conditioned. Some guys even slept there.

While the camp was in one of the most secure parts of the Da Nang area, occasionally at night the alert sirens would sound. If any place in the surrounding area was attacked everyone got an alert. We would then go out to the bunkers and stand around outside to see if there were any rockets landing close to us. If there were, we would go inside the bunker. If not, we stood around outside smoking and trying to avoid the shore patrol who drove around to make sure we were in the bunkers. Occasionally we could see an explosion or the path of tracers in the air. Mostly we could just hear them. We were never quite sure where they were, but we were fairly confident they weren’t very close.

One of the most entertaining things was watching the TV news reporters. Camp Tien Sha had a weapons repair facility. If you were near it, you could hear machine guns and other weapons being test fired after having been repaired. You could also see tanks and other armored vehicles running up and down their test track. We got a big kick out of watching reporters put on a helmet and a flak jacket and stand in front of the camera while the tanks ran up and down behind them and the machine guns fired and them saying: “I’m reporting from the front lines in Vietnam. You can hear the battle raging behind me “. Occasionally, we would laugh so hard that one of the production people would come over and run us off. I know we ruined more than a few shots.

Eventually I got called to the personnel office and was told that the Sanctuary was due in port that afternoon. They handed me my orders and told me to report on board. I asked how to get to the dock and the personnel clerk just looked at me and shrugged. I eventually found my way to the motor pool and got a ride with a jeep that was heading down towards the docks.

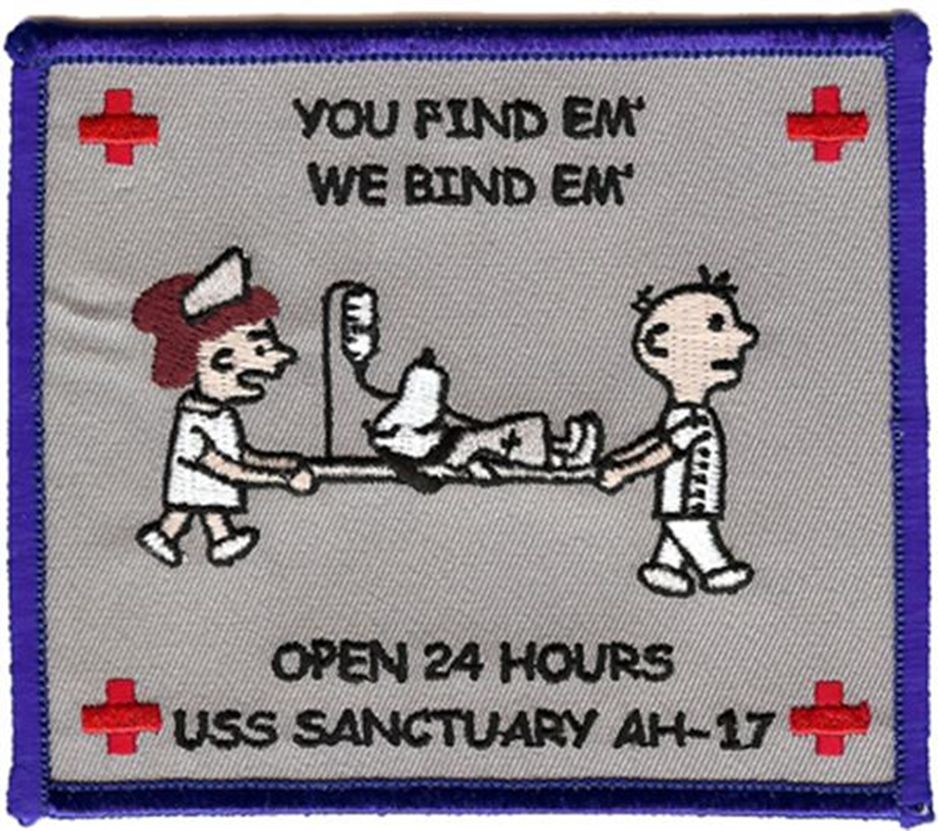

There were several ships in the port at that time. However, the Sanctuary was hard to miss. Unlike other Navy ships that were painted gray, the Sanctuary was painted bright white and was emblazoned with big red crosses on the hull. I walked up the gangway, saluted and requested permission to board. In Anchors Aweigh Part IV I’ll talk more about life on the Sanctuary.