Always has, always will.

Rock on!

Grumpy opinions about American history

Always has, always will.

Rock on!

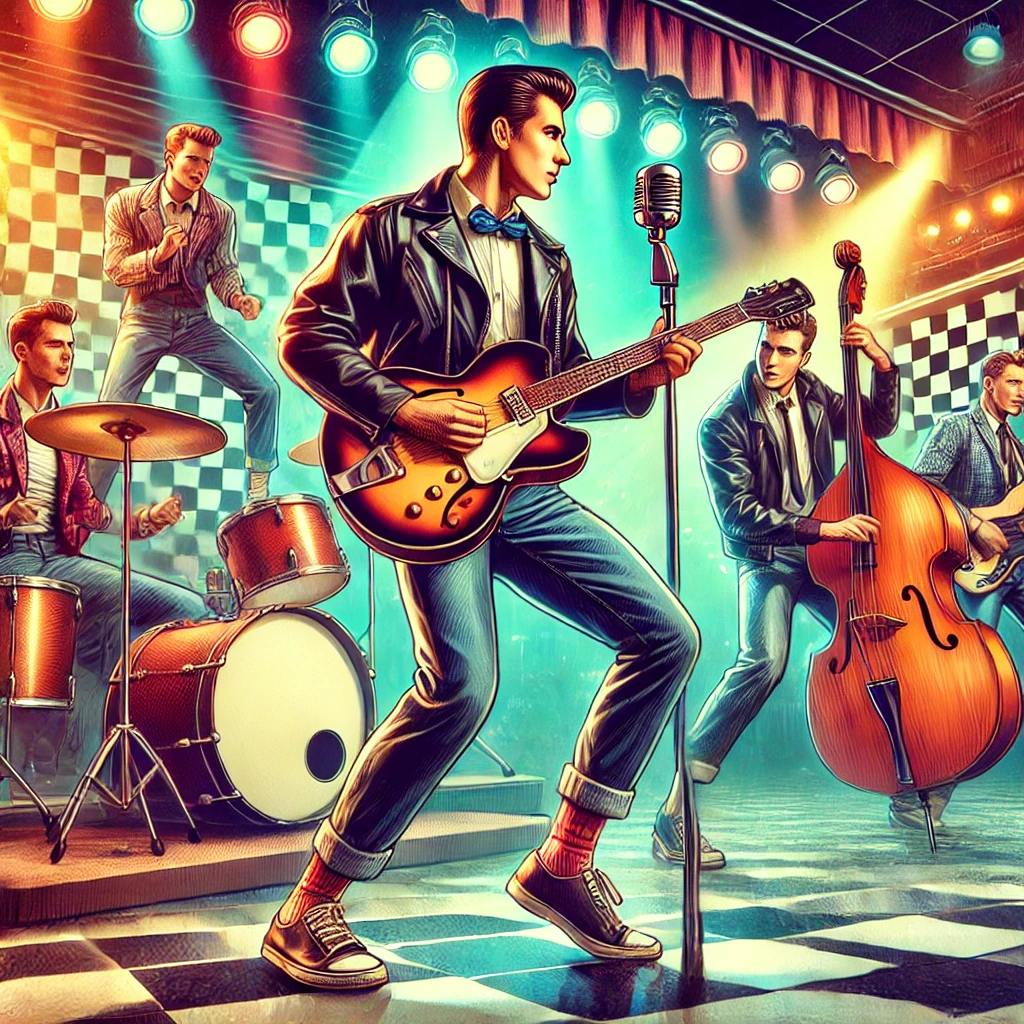

On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons From The Twentieth Century

Timothy Snyder

I don’t believe I have written a book report since I was a freshman in college. This is a small book that I believe is well worth your time to read. I mean small book quite literally. It’s about 4 1/2 inches by 6 1/2 inches and only about 126 pages of fairly wide spaced text. You can read the entire book in an afternoon and still have time left over. The book is also available as an audiobook, and it’s combined with Twenty New Lessons From Russia’s War On Ukraine. I got the audio book and listened to it as well. That will take about eight hours to complete.

I’m calling this a book report rather than a book review because I want to tell you what’s in the book rather than what I think about it so that you can form your own opinion. First, I’ll give you an overall impression. It’s thought provoking and raises issues of concern to us today. You may not agree with it. I don’t agree with everything that he said. I found some of his 20 lessons to be redundant because I thought he was stretching to get 20 lessons for the 20th century. I also found one or two of them to be painfully obvious. What follows is just a summary of the book. Read it and e-mail me or call me if you’d like to discuss it. I will send the book to the first person who asks for it, but only if you promise to pass it on when you’re finished.

Doctor Snyder is a professor of history at Yale University. He specializes in Central and Eastern Europe and has spent considerable time in Ukraine. He’s the author of 15 books and reads five European languages and can converse in ten.

Preface

The book begins with a preface in which Doctor Snyder establishes the importance of historical awareness. He describes the failure of some 20th century European democracies and their descent into authoritarian rule. He uses these examples to illustrate how democracy cannot be taken for granted. He makes the argument that democracy is fragile and must be defended. He further argues that even in the United States, the continuation of our democracy is not a given and we must fight for freedom and maintain constant vigilance over our democratic processes.

Each of his twenty lessons is contained in a separate chapter, varying from a few pages to a single sentence.

The Twenty Lessons

Epilogue

The book concludes with an epilogue entitled History and Liberty. In the epilogue Doctor Snyder discusses his theories of the Politics of Inevitability and the Politics of Eternity.

The Politics of Inevitability is the belief that history naturally progresses in a linear forward direction typically towards a better future. It assumes that liberal democracy and capitalism will inevitably spread across the world leading to a more prosperous and freer global system. Human forces are seen as predictable and human activity is often downplayed. People who live under the politics of inevitability tend to believe that the current state of affairs will persist because it represents the end point of political and economic evolution.

The Politics of Eternity, on the other hand, rejects the linear progression of history and emphasizes a cyclical view. It supposes that nations are perpetually threatened by external forces. It glorifies a supposed golden age of the past that is idealized and mythologized. It views current politics as a struggle to return to that idealized past.

I found his discussions to be more theoretical than practical. I can see aspects of both in most current societies. I invite you to please read this and I would love to discuss it. I may be missing something in his presentation of inevitability and eternity.

In Conclusion

If you are concerned about the survival of democracy, read this book.

Recently, I was listening to a series of lectures based on Democracy in America the classic review of politics and society in the United States during the 1830s. Alexis de Tocqueville (1805 – 1859) was a young Frenchman who visited the United States for nine months in 1831 and 1832. Ostensibly, he was here on behest of the French government to review the prison system. His personal goals were much broader.

He and a friend, Gustav de Beaumont, visited much of the United States. They interviewed citizens, reviewed documents, attended community meetings and observed federal, state, and local governmental activities of all branches: executive, legislative and judicial. They also collected books, newspapers, and documents. They visited cities and rural areas in the north and in the south. They even ventured as far as Wisconsin, then western edge of the American Frontier.

While they did produce a report on American prisons, which were then relatively progressive in the United States compared to the rest of the world, de Tocqueville had in mind all along that he would write a critique of the United States as he saw it. This eventually became a four-volume set published between 1835 and 1856.

I first became familiar with de Tocqueville when I read a much-abridged version of Democracy in America for an Early American History course. I believe it was probably about 250 pages. That is brief compared to the 926-page behemoth that I recently bought online.

I was interested not so much in what I remembered from my previous reading of his works as I was with what I didn’t remember. In particular, in one of his last chapters, de Tocqueville talks about the conditions under which despotism may arise in America.

As I have done previously with the writings of historic people, I’m going to present de Tocqueville’s writings in his own words without comment or analysis by me. Keep in mind that he wrote 180 years ago. It’s not as amazing that he got some things wrong, as it is how much insight he had into the problems that may potentially arise in America.

The excerpts in this post are from Book 4, Chapter 6: What Sort of Despotism Democratic Nations have to Fear.

I had remarked during my stay in the United States, the democratic state of society, similar to that of the Americans, might offer singular facilities for the establishment of despotism; and I perceived, upon my return to Europe, how much use had already been made by most of our rulers, of the notions, the sentiments, and the wants engendered by this same social condition, for the purpose of extending the circle of their power.

But it would seem, that if despotism were to be established among the democratic nations of our days it might assume a different character; It would be more extensive and more mild; It would degrade men without tormenting them.

I think then that the species of oppression by which democratic nations are menaced is unlike anything which ever existed before in the world: our contemporaries will find no prototypes in their memories. I’m trying myself to choose an expression which will accurately convey the whole of the idea I have formed of it, but in vain; the old words “despotism” and “tyranny “ are inappropriate: the thing itself is new; and since I cannot name, it I must attempt to define it.

The first thing that strikes the observation is an innumerable multitude of men all equal and alike incessantly endeavoring to procure the petty and poultry pleasures which they glut their lives. Each of them, living apart, is a stranger to the fate of all the rest – his children and his private friends constitute to him the whole world of mankind; as for the rest of his fellow citizens, he feels them not; exists but in himself and for himself alone; and if his kindred will remain with him, he may be said at any rate to have lost his country.

Above this race of men stands an immense and tutelary power… That power is absolute, minute, regular, provident, and mild. It would be like the authority of a parent, if, like that authority, its object was to prepare men for manhood; but it seeks on the contrary to keep them in perpetual childhood: it is well content that the people should rejoice, provided they think nothing but rejoicing.

… What remains, but to spare them all the cares of thinking and all the troubles of living?

After having thus successfully taken each member of the community into its powerful grasp, and fashioned them at will, the supreme power then extends its arm over the whole community. It covers the surface of society with a network of small, complicated rules, minute and uniform, though which the most original minds and the most energetic characters cannot penetrate, to rise above the crowd. The will of man is not shattered, but softened, bent, and guided: men are seldom forced to act but they’re constantly restrained from acting… It does not tyrannize but it compresses, innervates, extinguishes, and stupefies the people…

Subjugation in minor affairs breaks out every day, and is felt by the whole community indiscriminately. It does not drive men to resistance, but it crosses them at every turn, till they are led to surrender the exercise of their will.

It is in vain to summon the people, which has been rendered so dependent on the central power, to choose from time to time the representative of that power; this rare and brief exercise of their free choice, however important it may be, will not prevent them from gradually losing the facilities of thinking, feeling and acting for themselves and thus gradually falling below the level of humanity. It had that they will soon become incapable of exercising the great and only privilege which remains to them.

The nations of our time cannot prevent the conditions of men from becoming equal; but it depends upon themselves whether the principle of equality is to lead them to servitude or freedom, to knowledge or barbarism, to prosperity or to wretchedness.

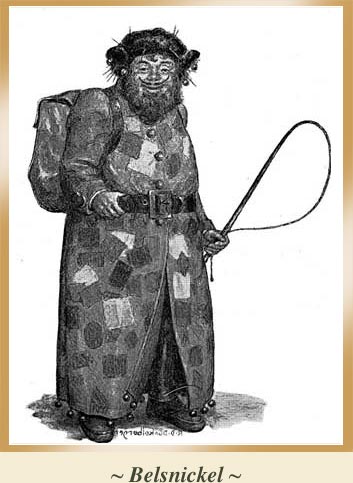

The illustration at the beginning of this post is not intended to be a portrait of de Tocqueville, but rather illustrative of the time.

Propaganda does not deceive people; it merely helps them to deceive themselves. Eric Hoffer

What is propaganda?

Propaganda! The very word conjures up images of sinister people involved in nefarious activities meant to delude the innocent. But this has not always been the case. Propaganda has, through much of history, been view as information, though frequently of a biased or misleading nature, used to promote or publicize a particular political cause or point of view.

Propaganda has always involved exaggeration and omission in order to achieve a specific goal. It was intended to shape beliefs and attitudes without actually lying to the listeners. At its core, there was a basis of truth.

We generally think of propaganda as the domain of governments. But, in its broadest definition, advertising might be considered as propaganda. It’s intended to create the impression that specific products contribute real advantage to your life. Drinking a specific beer will make you have a better time. Driving a certain car will show that you are more environmentally concerned. Wearing specific clothes will make you more popular.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that the incorporation of falsehoods, deception, and other activities intended to create a totally false impression and to promulgate untruths became the mainstay of propaganda.

Phillip Taylor in his book “Munitions of the Mind” presents an excellent history of propaganda from its origins in the early years of civilization through its rapid evolution in the 20th century, to its infiltration of all aspects of society in the 21st century.

Propaganda began as early as ancient Mesopotamia when the boastings of kings were inscribed on stone monuments. It continued, principally as a way of monarchs justifying their rule up through the 19th century.

The earliest use of the term propaganda was in the early 17th century when the Catholic Church, wishing to spread Catholic doctrine, support the faithful and counter the protestant reformation, established the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide).

World War I saw the beginnings of the disconnection of propaganda and truth. Both sides in that war created knowingly false narratives to bolster civilian morale and increase the fighting spirit of their soldiers. World War II took this process to a whole new level as false propaganda was used to justify mass murder and enslavement of an entire continent. In the 21st century propaganda techniques have been raised to a new level of technical sophistication. Social media, artificial intelligence and modern psychological techniques can create images, sounds and documents completely unrelated to reality but almost impossible for the average person to recognize as false.

Elements of propaganda.

One of the classic elements of propaganda is repetition, the more a statement is repeated the more likely people are to believe it. There is a concept called “illusory truth effect” where the more you hear a statement, the more it feels true.

In past centuries, reference was made to respected people in authority to give credence to statements. Over the years, this has evolved into celebrity endorsements and continues to expand with the recent emergence of instant celebrities in the form of social media influencers.

Emotional appeals have always been a significant part of propaganda, emotions being more easily manipulated than facts. The audience is encouraged to react rather than think.

Simplification is also a central tenant of propaganda; complex ideas are reduced to simple slogans that can be repeated over and over again. Slogans that are catchy and clever will encourage people to repeat them without considering their true meaning.

The repeated use of slogans contributes to the bandwagon effect, a critical propaganda technique for creating the impression of widespread acceptance. The more a person believes everyone else supports the program, the more likely they will be to support it without detailed personal analysis.

Evolving propaganda.

In the early years of the 20th century, propaganda began to take a more malicious path. It began to lose a grounding in truth, except where necessary to sell the lie. As propaganda evolved through the first few decades of the 20th century it became a specialized and highly effective weapon of statecraft.

It’s important to recognize that the ultimate goal of propaganda is not merely manipulating opinions and beliefs. It is a tool for obtaining and using political power.

The following quote, which I will leave unattributed, underlies the objective of propaganda from the mid-20th century on.

“All propaganda has to be popular and has to accommodate itself to the comprehension of the least intelligent of those whom it seeks to reach. The great mass of the people will more easily fall victim to a big lie than to a small one. If you tell a lie that is big enough and tell it frequently enough, it will be believed.”

Propaganda in Action

A propaganda program that is designed to achieve political goals has several key elements.

The Target

The first step is to decide on the target population. These are the people you wish to cultivate as supporters and whom you wish to manipulate into specific actions. It’s important to understand what they consider to be their critical concerns. Whether you share those concerns or not isn’t important if you are able to convince the target population that you care about them and that you will meet their needs. Once you have analyzed the concerns of your target population you can develop your message to best appeal to and manage their opinions.

The Leader

The second element is to create a cult of personality around the leader. Generally, the leader will be a charismatic and effective speaker. On other occasions, he simply may be someone they would “like to have a beer with”. If a bond can be created it doesn’t matter how. The leader doesn’t have to have a true concern for the target group as long as they believe he does. Once the leader and the target group have bonded, he will have an easier time manipulating them. The stronger they are connected to him personally, the less scrutiny they will give to his ideas.

The Others

The next element is to identify the “other” group that will be the focus of attacks. The first step is to create fear of this group. Once your target population has developed a significant fear of whatever this group may be accused of, be it crime, immorality, or “unAmericanism”, a program is put in place to demonize them. The purpose of the early program is to generate a high level of unreasoning fear of this group within the target population. Fear is difficult to control, so once this stage has been reached, the fear must be converted to hate through repeated attacks blaming the “others” for every grievance the target group has experienced. Hate is easier to focus and to direct. People can be more easily rallied to action, even violence, in response to hate.

Action

Once hate of the “other” group has been raised to a significant level, your target population can be moved to action. Be that unquestioning acceptance of ideas, voting for whatever candidates you identify, or even resorting to violence to suppress the “others”.

This is the stage where real political power begins to flow from your propaganda program. Your supporters have given up all efforts at critical thinking and blindly accept whatever orders you give in the misguided thought that you are concerned about them and their needs and are doing what is best for them and the country. They have become the weapon for implementing your agenda.

Conclusion

For those of you with an appreciation of history, this should resonate not only with the 20th century but with current events. If you would like to know the source of the quote I gave at the beginning of this section, contact me.

Having seen the effects of modern propaganda on our society, I am left in great despair. In a future post I’m going to be discussing how social media has significantly increased the rate of spread and the effectiveness of propaganda and other disinformation programs.

Over the past several months I have become increasingly discouraged as I watch the sad spectacle of the presidential election play out in the newspapers and on the electronic media. It seems the candidates are more interested in serving themselves than in serving the people. Each is convinced that he is the only one who can save the country. While one is obsessed with regaining the power of the president, the other is reluctant to relinquish it.

This has left me wondering if there’s not a better way to elect the president. As everyone knows we elect a president for four years and then they can be reelected for an additional four years. But this was not always the way our electoral process has been structured.

A brief history of presidential terms

Perhaps second only to slavery, the office of president was one of the most controversial subjects at the 1787 Constitutional Convention. There were extensive debates about the structure of the office, the power of the chief executive, and even if it should be a single person. There was a proposal put forward by Edmund Randolph of Virginia for a three-person executive committee to head the government.

There were proposals for a short-term presidency of one or two years, arguing that more frequent elections would ensure the chief executive was more responsible to the people. There were also proposals for longer terms such as 7 or even 15 years. The intent of longer terms was to provide the president with independence from the influence of special interests and provide for more stable government.

There is a popular misconception that Alexander Hamilton favored a president for life. While he advocated for a strong presidency with certain aspects of a monarch, he also recognized the importance of a fixed term and the provision for impeachment to safeguard the country against abuse of power.

After it became clear to most delegates that George Washington would become the first president, the convention decided on a four-year term for the president. The constitution as originally adopted did not explicitly state that the president can be reelected, nor did it prohibit reelection. Not all delegates were in favor of allowing the president to be reelected because they felt it would result in too much power being consolidated the hands of the single person. As often happens in politics, no decision was made, and the Constitution as adopted was silent on reelection.

The issue of term length did not end with the ratification of the constitution. The first proposed constitutional amendment to change the length of the presidential term was introduced in 1808. Since then, multiple amendments have been proposed to extend the term to five, six, seven or even eight years. By the early 1900s the single six-year term had become the dominant idea being proposed. Amendments to change the term of the presidential office were introduced as late as the 1990s. Although persistent in their reappearance, none have ever had any realistic chance of being approved.

George Washington set the precedent of serving only two terms by retiring to Mount Vernon at the end of eight years in office. This pattern was followed until Franklin Roosevelt ran for a third and then a fourth term. After Roosevelt’s death, the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution was passed by Congress in 1947, and ratified in 1951, limiting the president to two total terms in office.

Other countries have different patterns for their chief executive’s term of office. Parliamentary countries have no set term. Elections can be called, and the chief executive removed from office whenever confidence in the government has fallen, and the public demands a change. Other countries such as Mexico, the Philippines and Chile have a single six-year term for president.

If we were to consider a single six-year term for the US president how would that change things. Let’s look at a few of the pros and cons.

The arguments in favor of a single six-year term

The president would be relieved of the burden of an almost constant reelection campaign. With a single term, a president can focus on policy and governance without being distracted by the next election cycle. This may lead to bolder, more decisive leadership, unencumbered by the need to cater to special interest groups. Those groups may be less inclined to make large political contributions knowing that they hold no future sway over the actions of the president.

There may be potential for greater continuity in policymaking. Presidents could be more inclined to tackle unpopular long-term challenges head-on, rather than deferring them to a second term or even to their successor. The president may be more likely to engage in bipartisan programs knowing that there is no need to appease party radicals during a reelection process. The president could be more likely to engage in long term planning rather than worry about what will look good in the polls in the short term. This may result in fewer political decisions made just to improve reelection chances.

Not having to run for reelection would also give the president more time to work for the country and the citizens. The time and the effort put into planning campaigns, making speeches, and attending reelection events could be spent improving the government and the country. If the president has more time to work closely with Congress, then there could be less gridlock in Washington. In sum, the single six-year term may allow the president to be the statesman they all claim to be.

The arguments against a single six-year term

A single six-year term could diminish the accountability of the president to the electorate. In a traditional two-term system, presidents are incentivized to deliver on their promises and perform effectively to secure re-election. With only one term to serve, there may be less pressure for a president to maintain high levels of performance throughout their tenure. This could result in complacency or a lack of motivation to pursue ambitious reforms, knowing there won’t be a chance for the electorate to hold them accountable.

A single six-year term could disrupt the balance of power between the executive and legislative branches. With the absence of a potential second term, presidents may become more inclined to bypass Congress and govern through executive orders and unilateral actions. This could lead to increased polarization and gridlock, as Congress may resist executive overreach, exacerbating tensions between branches of government.

If the president proves to be inept or not acting in the best interests of the people and the nation, six years is a long time for that person to be in office. The only option would be impeachment and we know from recent experience that impeachment is a long and painful process frequently generating more ill will than good results.

And in conclusion…

So, would a single six-year presidential term be a good thing or a bad thing? Would it help us get out of our current political mess?

Perhaps it would have no impact at all. Perhaps it’s not the length of the presidential term, the number of terms the president serves, or even how we elect the president. Perhaps the real problem lies with us. It doesn’t matter how we elect our president if we don’t do a better job deciding who the candidates will be. It’s been said many times that people get the government they deserve. We all complain about it and yet we continue voting for the same type of people year after year.

Of all the people to blame for the current political situation, the one in the mirror is the one to whom we should look first. Because, after all, that’s the only person we can control.

And that is my grumpy opinion.

So why should we consider myths as anything but an anachronistic curiosity since we consider ourselves a rational and scientific society? Because the willingness to believe in myths is as strong today as it has ever been. While belief in Olympian gods, elves, and fairies has faded away new myths have arisen. Since the late 1800s, at least two new myths have spread in the United States.

The Golden Age of America

Our political situation today has much to do with belief in the Myth of the Golden Age of America. I strongly believe that the United States has been and continues to be the best hope for personal freedom in the world today. But the idea that at some time in the recent past everything was wonderful for everyone is a myth. In this “Golden Age” to which some people wish to return, women, minorities, gays, and the disabled were clearly discriminated against.

One key contributor to the Golden Age Myth was the economic boom that followed World War II. The United States was a global industrial leader and the economy showed significant gains in jobs, wages, and consumer goods. The middle class was expanded, college education rose due to the GI Bill, and home ownership reached new levels. However, these advantages did not reach all members of our society.

Racial minorities continued to be actively discriminated against. Segregation, particularly under the Jim Crow laws in the South, limited economic, social, and political opportunities for our Black citizens.

Women’s roles and opportunities similarly were significantly constrained. Women were expected to take a domestic role over professional or personal aspirations. Even women who obtained advanced college degrees were expected to stay at home and raise their family or to take “appropriate” jobs such as secretaries, teachers, or nurses.

Reaction to the Golden Age Myth led to movements such as women’s liberation and the civil rights movement, both followed shortly by gay rights and the advocacy for the disabled. The Golden Age seems to have existed principally in popular television shows such as Ozzie and Harriet or Father Knows Best. In short, this “Golden Age” was not golden for everyone.

The Lost Cause

This myth arose in the South in the late 19th and early 20th centuries though it had its origins while the war still raged. According to the Myth of the Lost Cause, the Civil War had nothing to do with slavery. It had to do with the southern states fighting for their individual state rights and their prerogatives of self-government. They were fighting against northern aggression that was trying to destroy the southern way of life. Most Confederate soldiers were poor farmers who neither owned nor could afford slaves. They had to be convinced that they were fighting for their way of life against a malicious union army that was intent on invading their homes and forcing “northern ways” on them. The soldiers had to be distracted from the fact that they were fighting, suffering, and dying to protect the way of life of the wealthy slave owning aristocracy.

The evolution of legend was also involved in the creation of this myth. Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson were idealized as true southern gentlemen struggling in a glorious but doomed battle against overwhelming odds.

Of course, it completely ignores the fact that the southern way of life and those state rights were predominantly based on slavery. A critical element in this myth is that slavery was good for the slaves. We continue to hear this stunning falsehood from politicians today as they try to describe slavery as a little more than job training.

Many historians today agree this myth is an intentional distortion of historical facts. The Lost Cause Myth reached its fully developed form in the years surrounding the turning of the 20th century and was intended to change the historical narrative of the South’s role in the Civil War by minimizing the central role of slavery in the origin of the conflict. This revisionism was part on the broader social effort used to justify segregation, Jim Crow laws, and white supremacy.

The Lost Cause is a compelling example of history being reshaped by myth and legend. It shows how over time people can come to accept those things that most support their personal beliefs despite evidence to the contrary. It continues to dominate much of our current debate about race relations, voting rights and social welfare policies. However, today open advocacy of the Lost Cause Myth is in the background and it is seldom mentioned by name though its tenents are reflected in the opinions and statements of many .

Why believe in myths?

So why do we have a widespread belief in these myths? There are several reasons people persist in a false belief even after it has been largely disproven.

The most obvious reason is that myths meet emotional needs. They can be deeply ingrained in a person’s identity, beliefs, and values. When the myth is tied to political or religious beliefs people will be resistant to change even in the face of contradictory evidence. Admitting a previous error of belief is, in some ways, viewed as a form of weakness.

There is also a condition called confirmation bias. People are inclined to seek out and accept without question things that confirm their pre-existing beliefs and opinions. They ignore anything that is not consistent with an already held position.

When presented with information that conflicts with previously held opinions, people can experience what is known as cognitive dissonance. This is the emotional distress that people feel when attempting to hold two contradictory ideas or when trying to reconcile new information that challenges their behaviors or previously held ideas. To reduce this distress people either ignore or in some cases violently reject anything that conflicts with what they previously believed.

Critical thinking skills involve objectively evaluating evidence, identifing inconsistencies, and appling reasoning skills. Critical thinking isn’t always a natural process. When I was in high school, we were expected to memorize facts and then duplicate them on tests. I don’t remember even hearing the term critical thinking until I was in graduate school. Even then, I’m not really sure I understood how important it is to develop a personal understanding of facts and events and how difficult it would be to aquire those skills.

Teachers now make an effort to teach critical thinking skills. But it can be difficult for students to translate those skills into their life outside the classroom. Perhaps many of them may think of critical thinking the way they think of algebra, something they must do in school but won’t ever use in their everyday life. A well-informed citizenship requires all of us to encourage critical thinking practices. We need to ensure that our young people are reading and listening and using those skills outside the classroom. It’s easy to say, but venturing out of our comfort zone can take strength and purpose for all of us.

We can quickly fall into the habit of listening to or reading only a narrow range of opinions from a limited number of sources. It is particularly easy when those sources don’t challenge us to think or to analyze. It is too easy to reject new information rather than trying to evaluate and reconcile it with our previously held beliefs.

Obviously, these reasons are not mutually exclusive and are melded into a continuum of reasons for the rejection of fact in favor of myth.

Both the Lost Cause Myth and the Golden Age Myth arose much quicker and for a more limited purpose than did the classic myths. In this way the evolution of these myths has much in common with the concepts of propaganda. In my next post I will be looking at the difference between lies and myths and how both relate to propaganda and how it has evolved in modern times.

A brief history of myths and legends

This is the first in a series of posts on myths, legends, lies, and propaganda. Above are illustrated Thor, Paul Bunyon, and Zeus. Instinctively we know Thor and Zeus are myths and Paul Bunyan is a legend. But how do we know that?

Let’s start with the Merriam-Webster definitions.

Myth: “a usually traditional story of ostensibly historical events that serves to unfold part of the world view of a people or explain a practice, belief, or natural phenomenon”. Legend: “a story that comes from the past, especially one that is popularly regarded as historical but not verifiable. Legends are also traditional but unfounded stories that explain the reason for a current custom, belief, or fact of nature.”

As with many dictionary definitions, these are broad and give the general concept without developing any detail. One important element is included in the definition of both; they are based on traditional stories that have evolved through shared historical experiences and understandings. They are generally not created as a single fully developed narrative. Almost all cultures have a tradition of myth and legend. For example, the “creation” myth is surprisingly similar among diverse societies.

So, how do we differentiate between the two?

Myths are primarily religious or spiritual in nature and evolve to help people understand the mysteries of the physical universe. They typically involve supernatural beings represented as “gods”. For example, early people did not understand that the rotation of the earth caused night and day. As a way of dealing with this they created the myth of a god driving a flaming chariot across the sky.

Legends, on the other hand, are usually based on a historical person or are, perhaps, a synthesis of several people into a single legendary figure. They are less about the supernatural or divine but more about human heroes who accomplished extraordinary deeds. Legends evolve over time with the hero frequently accomplishing great feats that reflect the concerns of the population at the time. The legends are intended to inspire and to contribute to societal cohesion. The legend can have variations in many areas over many years. The classic example of this is the King Arthur legend which comes in many forms in different countries spanning several centuries. Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett are examples of historic Americans who have evolved into near legendary status.

As you might expect, myths and legends can overlap and can even melt into one another. They can also be incorporated into propaganda and can be used to support false narratives of history and society. For the rest of this post, I’m going to principally look at myths because of their similarity to legends and because sometimes it may be less clear that the origins of some belief may be steeped in mythology or legend.

More About Myths

Myths serve a variety of purposes. They are used to explain natural events that are not well understood. A variety of “gods” were created to help people feel they had a sense of control in a world that seemed very dangerous to them. They helped people feel there is a purpose to existence.

Myths also help shape cultural and social identities. They give people a sense of shared history and reflect community values and customs. The myths frequently contain ethical and moral lessons. Myths help create unity in times of difficulty and can be a source of inspiration. Myths can also be used as an object lesson about what could happen to those who don’t respect community values.

In preliterate societies, myths performed a service of historical or cultural preservation, particularly as it relates to behavior and beliefs. Myths frequently use symbolic language and narrative to enhance societal cohesion. They reinforce a feeling of belonging within the group.

Myths can have an emotional appeal and are more engaging than a dry listing of facts. They can often provide a simple answer to complex problems. Societies find comfort in the stability that an underlying myth can provide even if there is no empirical evidence to support it. Myths can become so embedded in a society’s religion, art, and literature that some people often have trouble separating the myth from the reality of the world around them.

The belief in myths is not always consistent among groups and cultures. In some societies, myths are taken literally while in others they are taken allegorically. The belief in myths has changed over time as societies have evolved knowledge and scientific understanding. But they all share an attempt to transform the metaphysical to the literal.

While the evolution and perpetuation of myths was of great value to early societies, continued reliance on myths as a source of knowledge often hampered scientific development. Throughout history, there have been persecutions of people who proposed new scientific knowledge or philosophical opinions that varied from society’s foundational myths.

We tend to think of myths as having arisen in the mystic past. We think of them as entertaining stories with little relation to our lives. However, myths continue to evolve, and new myths are continually created. In my next post, New Myths Arise, I’ll talk about two myths particular to the United States that have risen within the last 150 years and still have a continuing impact on our society.

François de La Nouea, a Huguenot Captain

Today’s post is a guest column by my wife Margie. This first appeared in the January 2024 issue of the newsletter of the Daniel Boone Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution.

One day I received an interesting text from my cousin, Mary. She had been accepted into the Huguenots Society and said that due to our lineage, I could be a member. So, with her help, I am now a member. The Huguenots were French Protestants who were active in the 16th and 17th centuries. They were forced to flee France due to religious and political persecution. The Huguenot Society of America was founded in 1883 to perpetuate the memory of Huguenot settlers in America. George Washington was the grandson of a Huguenot on his mother’s side. I am a descendant of Barbara de Barrette who was a Huguenot and lived in Valenciennes, France, around 1657. She married Garrett Van Swearingen and they settled in Maryland. Last October John and I enjoyed going to the 2023 Huguenot Society of America Conference in Macon, Georgia. We had never been to Macon and enjoyed meeting fellow members and visiting historic landmarks such as the Hay House and the Cannonball House and, of course, eating great southern cuisine. Check the internet to find out more about the Huguenots. It is very interesting reading and who knows, you, too, may qualify as a member!

If you would like to contribute a guest post, please contact me. The Grumpy Doc can always use a little help from his friends.

In the United States today, we have a very expansive view of what constitutes Christmas celebrations. We don’t find it at all unusual to see an inflatable Santa Claus next to a manger scene. The wisemen are as likely to be following neon snowflakes as yonder star. This combination of religious and secular is something that we just accept without a whole lot of thought. But it wasn’t always the case. In colonial America Christmas was celebrated in a mostly religious fashion when it was celebrated at all.

Colonial New England

Colonial New England was settled in large part by Puritans. They even extended their influence to areas that they did not initially settle. They went so far as to banish, and in some cases even execute people who did not agree with them. They were determined to create a society dominated by Puritan beliefs.

The Puritans did not favor Christmas celebration; they believed there was no scriptural basis for acknowledging Christmas beyond doing so in prayer. In 1621 Governor William Bradford of Plymouth Colony criticized some of the settlers who chose to take the day off from work because as Puritans he felt that they could best serve God by being productive and orderly.

The celebration of Christmas was outlawed in most of New England. Calvinist Puritans and some other protestants abhorred the entire celebration and likened it to pagan rituals and “Popish” observances. In 1659, the General Court of Massachusetts forbade, under the fine of five shillings per offense, the observance “of any such day as Christmas or the like, either by forebearing of labour, feasting, or any such way.” The Assembly of Connecticut, in the same period, prohibited the reading of the Book of Common Prayer, the keeping of Christmas and saints’ days, the making of mince pies, the playing of cards, or performing on any musical instruments. These statutes remained in force until they were repealed early in the nineteenth century.

It is important to note that Puritan hostility to Christmas was not because they did not believe in the divinity of Jesus Christ. They objected to the way the holiday was being celebrated. They disliked the excesses of Yuletide festivities in England. Christmas had become a time for the working class to drink, gamble, and party. The Puritans would not tolerate any sign of disorder and believed that it was an affront to God.

They tried to protest Christmas revelries while still living in England but had little impact. Once they moved to the New World where they were able to exert control, they would not condone any form of excess. Except, perhaps, an excess of piety and self-righteousness.

Any form of Christmas observance that did occur took the shape of fasting, prayer, and religious service. Even the famous New England cleric Increase Mather loathed Christmas and believed the holiday was derived from the excesses of the pagan Roman holiday Saturnalia. We shouldn’t think that Mather was completely humorless; he once called alcohol. “a good creature of God “. Drinking wasn’t bad, but like all things it must be done in moderation with complete self-control. That’s probably good advice for everyone, whether they’re a Puritan or not.

Middle Atlantic Colonies

Many of the traditions that we now consider part of the American Christmas have their origins in the middle Atlantic colonies, most notably in Pennsylvania. Many of these were brought by settlers of German heritage as well as some traditions brought by the Scots and the Dutch.

In Pennsylvania there were two quite different Christmas traditions, one of the protestant groups and another of the Quakers. They differed considerably in their approach to Christmas.

Some colonists celebrated Christmas by importing English customs such as drinking, feasting, mumming and wassailing. Mumming involved wearing masks and costumes and going door-to-door singing carols or performing short plays in exchange for food or drink. Wassailing was a tradition where people would go from house to house singing carols and drinking toasts to the health of their neighbors. Some non-Puritan New Englanders also continued these traditions but kept them private to avoid attracting the attention of the Puritan officials.

Many of the Christmas traditions that we think of as being a quintessentially American are derived from the settlers of German descent who were known as the Pennsylvania Dutch. These include celebration of the advent season, the decoration of the Christmas tree, singing of Christmas carols, the display of nativity scenes, and the exchange of gifts on Christmas Eve or Christmas morning. We can’t imagine Christmas without these things, but we seldom remember that it was our German American ancestors who gave us these wonderful traditions.

To me the most interesting and probably most significant tradition passed on by the Pennsylvania Dutch was what led to our current concept of Santa Claus. During the colonial period, they had the tradition of Beltznickle. He is depicted as a man wearing furs and a mask and having a long tongue. He’s usually shown as being very ragged and wearing dirty clothes. He had a pocketful of cakes, candies and nuts for good children, but he also carried a switch or a whip with which to beat naughty children. Beltznickle took the naughty and nice list very seriously.

He was a long way from Clement Clark Moore’s jolly old elf in ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas and the jovial Santa Claus that we know today from the original Coca-Cola ads of 1930.

Quakers had a much different approach to Christmas. They did not celebrate it at all. It is not that they were opposed to Christmas as were the Puritans. It’s just that they did not celebrate any holidays, Easter, birthdays or any other holidays. They had no set liturgical calendar, so they did not have an advent, or an Easter season or any other religious holiday. There is no central Quaker authority to set beliefs or doctrines. Each Quaker is free to decide how to observe religious traditions. They focus on spiritual reflection and social justice.

Non-Quakers did not always understand their religious beliefs or practices. Here is an example of how Quaker practices were seen by outsiders. Swedish naturalist Peter Kalm visited Philadelphia in 1747 and recorded the following observation in his diary:

Christmas Day. . . .The Quakers did not regard this day any more remarkable than other days. Stores were open, and anyone might sell or purchase what he wanted. . . .There was no more baking of bread for the Christmas festival than for other days; and no Christmas porridge on Christmas Eve! One did not seem to know what it meant to wish anyone a merry Christmas. . . at first the Presbyterians did not care much for celebrating Christmas, but when they saw most of their members going to the English church on that day, they also started to have services.

Apparently, Presbyterians were much quicker to adopt popular practices then were the Quakers.

Southern Colonies

Celebration of Christmas was similar throughout all of the southern colonies. We’ll consider Colonial Williamsburg as a proxy for the rest of the southern colonial region. This is largely because there is more information available about Williamsburg than other areas and because it represented what was the majority of practices at the time. The major religion of the southern colonies was Church of England and they followed those practices.

Religious services were a central part of their celebration. The majority of the religious observances were during the advent season, the four weeks leading up to Christmas which were a period of reflection on the significance of the coming of Christ. The southern colonies usually held Christmas Eve services although occasionally Christmas Day services were held. Christmas Day was considered a day of celebration and family feasting.

It should be noted that the Christmas celebration was only for the white population. If the enslaved people received a holiday for Christmas, it was only because the weather was too bad to work in the fields. And of course, the house slaves were expected to attend to all the needs of the Christmas celebration.

Margie and I decided to visit Colonial Williamsburg in December of 2019, the period we refer to as BC (before COVID). We’ve always had a special affinity for Williamsburg because that’s where we spent our honeymoon 52 years ago. I’m not sure exactly what I was expecting, perhaps a large inflatable George Washington holding a Christmas wreath. But it was much more understated than what I had anticipated.

According to our tour guide, even those low-key decorations were probably more than would have been evident in the colonial era. People typically decorated their homes on the day before Christmas and removed the decorations the day after Christmas. Decorations were usually limited to candles in the window and pine boughs on the tables and mantle pieces. Pine boughs were used to decorate the church in what was known as “sticking the church”.

At Colonial Williamsburg we saw many displays that included fresh fruits and pineapples. Our tour guide told us that those were too precious to actually have been used as decorations and might have been included as part of a table display to be consumed during the Christmas feast. Some people would even rent a pineapple to display on their table as a sign of their wealth.

The first Christmas tree did not make its appearance in Williamsburg until 1848.

The southern colonists were very social people. They enjoyed wassailing as did the people of the mid Atlantic colonies. They also considered Christmas as a time for feasting, dancing, and celebrations. Men of the upper class celebrated Christmas with fox hunts and other outdoor activities. Men of the working classes frequently celebrated Christmas with shooting matches and drinking parties. Women, of course, were expected to stay at home and prepare the meals. Christmas Balls were a common practice among the upper class of the southern colonies. They were often elaborate and included large banquets with musicians, dancing and occasionally masquerades.

Present exchange was not standard practice in the southern colonies. However, it was common to give children small presents of nuts, fruit, candy, and small toys. Adults generally did not exchange presents.

Virginian Phillip Fithians writing in his journal in 1773 gave the following description of a gather just before Christmas: When it grew to dark to dance. . . . we conversed til half after six; Nothing is now to be heard of in conversation, but the Balls, the Fox-hunts, the fine entertainments, and the good fellowship, which are to be exhibited at the approaching Christmas.

Life in colonial America could be hard, but that did not stop them from having a joyous Christmas celebration.

Powered by WordPress & Theme by Anders Norén

What Would George Washington and Thomas Jefferson Think About Our Current Political Climate?

By John Turley

On October 16, 2024

In Commentary, History, Politics

In considering what George Washington and Thomas Jefferson might think of today’s political situation, it’s tempting to view their perspectives through the lens of nostalgia, believing that the founders had an idealistic vision that, if followed, would have prevented many modern problems. It’s impossible of course to know what they may have thought about our current environment. Certainly, such things as a 24-hour news cycle on cable television and social media would have been beyond their comprehension. While both men lived in a vastly different era, their writings and philosophies give us a sense of how they might respond to the polarization and tensions we witness today.

George Washington: A Warning Against Partisanship

George Washington was deeply concerned about the rise of factions in the United States. (Political parties as such were unknown at the beginning of our republic.) In his famous Farewell Address in 1796, he warned that factions could lead to division and weaken the unity of the country. Washington was worried that faction (party) loyalty would surpass loyalty to the nation, creating conflict between groups and impairing the ability of government to function for the common good. He feared that excessive partisanship would “distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration,” leaving the nation vulnerable to foreign influence and internal discord.

If Washington could observe today’s political environment, he likely would be saddened by the partisanship which dominates political discourse. The gridlock, belligerent rhetoric, and divisiveness we experience today demonstrate the appropriateness of his concern. Washington would likely advocate for a return to greater civility, urging Americans to focus on the common good and to set aside factionalism for the sake of national unity. While political parties have become integral to our system, Washington would likely still press for cooperation, mutual respect, and compromise among all groups.

Thomas Jefferson: Liberty, Democracy, and the People’s Role

Thomas Jefferson, while more supportive of political parties than Washington, had his own complex views about governance. Jefferson believed in the power of the people to govern themselves and was a passionate advocate for liberty, democracy, and decentralization. He distrusted concentrated power, whether in government, or economic institutions, and feared that it could lead to tyranny. Jefferson was famously a champion of agrarianism and believed that widespread participation in the democratic process was the best defense against corruption and the loss of liberty.

Jefferson, while a proponent of states’ rights and individual liberties, might view polarization as a threat to democratic ideals if it stifles dialogue and compromise. He believed in the potential for free men to govern wisely, but would caution against the erosion of civil discourse that might follow the rise of extreme factionalism

Faced with the highly charged political debates of today, Jefferson would likely express concern over the increasing centralization of power in government, banks, and large corporations. He would, without doubt, be troubled by the outsized influence of money in politics.

Jefferson was also a firm believer in education as a cornerstone of democracy; he would stress the importance of an informed electorate, particularly in an age where misinformation can spread rapidly.

However, Jefferson was no stranger to political conflict, having played a central role in the fiercely partisan battles of his time. He understood the value of vigorous debate but would probably urge that such debate remain focused on the core democratic principles of liberty, justice, and equality rather than devolving into personal attacks.

Media and Civil Discourse

Of course, it is impossible to know what Washington and Jefferson would think about the current role of media, particularly social media which would be beyond anything in their experience. Washington felt strongly aggrieved by the attacks upon him in the newspapers of the time. He felt unfair attacks would undermine national unity. Jefferson, on the other hand, was a strong proponent of freedom of the press. He was also very adept at the use of newspapers to accomplish political means.

However, it is likely that both would caution against the dangers of misinformation and partisan bias to distort public perception. Most likely both would emphasize the need for a responsible press that distinguishes between fact and opinion and supports a healthy democracy. Both would be opposed to using false or misleading statements to influence the public.

Unity and Civic Responsibility

Despite their differences, both Washington and Jefferson would likely agree on one thing: the importance of unity and civic responsibility. They envisioned a country where citizens were deeply involved in a participatory government, contributing not just with votes but with informed, constructive dialogue. Washington would call for a spirit of national unity above party lines, while Jefferson would insist that the preservation of liberty relies on active and informed participation from the public.

Both founders would encourage a healthier, more cooperative political environment, one where differences are respected and not allowed to fracture the country. They would likely see today’s polarization as a threat to the very ideals they fought to establish, and both would urge Americans to remember their shared values.

Conclusion

In short, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, while men of their own time, had insights that are still relevant today. Neither man could have predicted the exact nature of modern politics, but their wisdom offers enduring guidance: political disagreements must not undermine the unity, liberty, and civic responsibility that are the foundation of the American experiment. We owe it to them not to lose the promise of the American Revolution.