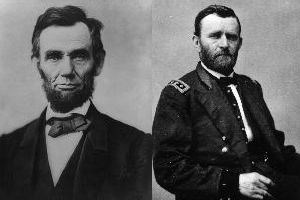

On January 12, 1864, President Lincoln went to Fort Stevens north of Washington, DC to observe military actions by the soldiers defending the capital against the Confederate cavalry of General Jubal Early. Lincoln became the only sitting United States President to come under direct fire from enemy troops. Reportedly, a young officer named Oliver Wendell Holmes (a future Supreme Court Justice) said to Lincoln “Get down you, damn fool”.

Ulysses S. Grant was the first army officer to hold the rank of Lieutenant General since George Washington.

One of General Grant’s ongoing problems was political generals. Because the army expanded so quickly, many people with little or no military experience were commissioned as officers because of political connections. Former senators, congressmen and governors frequently became generals. A number of these were placed in critical combat commands. Many of the early union setbacks can be partially attributed to the ineptitude of political generals who either were unable or unwilling to follow the orders of the professional army. (It must also be admitted that a few regular army generals were inept, but they were easier to set aside.) It wasn’t until late in the war that Grant finally had sufficient influence to be able to dismiss a number of these political generals.

Future Confederate General James Longstreet was a groomsman at the wedding of Ulysses and Julia Grant. He was a West Point friend of Grant’s and Julia’s cousin as well.

Lincoln first offered command of the Army of the Potomac to Robert E Lee. Lee refused, resigned his commission in the United States Army, and returned to Virginia where he swore allegiance to the Confederacy. The first official commander of the Army of the Potomac was General George B. McClellan. General Irwin McDowell commanded the union forces at the first battle of Bull Run, but those forces had not been designated as the Army of the Potomac at that time.

Lee was not the first choice for command of the army of Northern Virginia. The first commander of what would eventually become the army of Northern Virginia was General P. G. T. Beauregard. Interestingly, he also designed the Confederate battle flag which is today widely considered as the “Confederate flag”. It was designed because of the confusion between the Confederate national flag, the stars and bars, and the United States flag. General Beauregard relinquished command to General Joseph E. Johnston when his army was combined with Johnston’s larger army group. Lee did not become commander of the army of Northern Virginia until Johnston was wounded in battle and unable to continue.

The Civil War did not end with the surrender at Appomattox Courthouse on April 9, 1865. On April 26th, Joseph E. Johnston surrendered his larger army of 90,000 soldiers. On May 26th General Kirby Smith surrendered the Army of the Trans-Mississippi, the largest confederate force still operating on land. The last Confederate flag was lowered when the open ocean raider CSS Shenandoah surrendered to the British in Liverpool on November 6th. Interestingly, almost half of the Shenandoah ‘s victories over merchant ships occurred after the surrender at Appomattox.

The surrender at Appomattox Courthouse occurred in the home of Wilmer McLean. In one of those interesting coincidences of history, McLean originally lived near Manassas VA and his property was part of the battlefield of Bull Run. He moved to Appomattox Courthouse to try to get as far away from the fighting as he could.

At the beginning of the Civil War, Ulysses S. Grant was not even in the army. Initially, despite being a West Point graduate, he was refused a commission in the regular army and his first Civil War commission was in the militia.

Grant and wife were initially scheduled to be in the box with President and Mrs. Lincoln at Ford’s Theater on the night the President was assassinated. At the insistence of Julia, the Grants left Washington that afternoon. There’s been much speculation about why they did not attend the theater. Among the many reasons put forward are: Julia missed her children whom she had not seen for almost three months; Julia did not wish to spend time with Mrs. Lincoln whom she found disagreeable and with whom she had several contentious meetings; and one which seems most interesting, she was reported as being very worried about someone that she thought had been watching her all that day and she felt they needed to get away. The assassins did report that Grant had been one of their initial targets so this may be a true report.

Emancipation Proclamation only freed slaves in Confederate held territory. Slavery was not officially abolished in the entire United States until December 6, 1865, with the ratification of the 13th amendment.

Counting both northern and southern casualties, more Americans died in the Civil War than in all other American wars combined. The most recent estimate of the number of Civil War deaths on both sides is placed at about 750,000. Of that number, almost 2/3 died from disease.

At the end of the Civil War the United States had the largest army in the world. In 1860 the US Army had been about 16,000. At the end of the Civil War, it is estimated the army was slightly over one million. It is estimated that a total of about 2.6 million served in the US Army during the Civil War. There are no reliable estimates of the total number to have served in the Confederate Army.

Grant’s drinking was largely overstated. The stories of his dinking stem from a period, early in his career, when Grant was assigned to an isolated fort on the West Coast and his family remained on the East Coast. He suffered depression and loneliness. Throughout his life he had anxiety when separated from his family. While in the west, he began bouts of binge drinking. He missed his family to the point that he resigned from the army even though he had no job prospects at the time. There is very little report of any drinking by Grant’s following his return to the army during the Civil War, although rumors were plentiful. When given reports of supposed excessive drinking on Grant’s part, Lincoln is reported to have said “Find out what whiskey he drinks and send a case to all of my generals”.

Grant smoked up to 20 cigars a day and admirers from all over the country mailed him boxes of cigars. He eventually died of cancer of the throat and tongue.

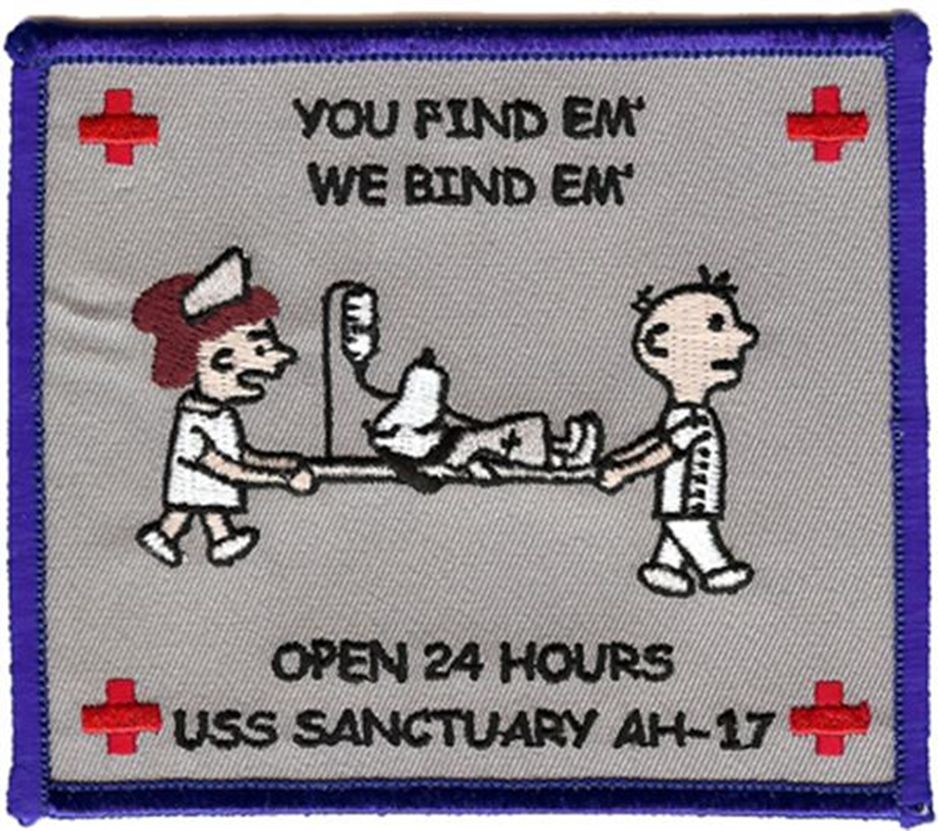

The poet Walt Whitman worked as a volunteer in union hospitals.

Lew Wallace, author of Ben Hur, was a general in the Union Army. By most reports he was a better author than general.

The last verified Civil War veteran died in 1956. He was Albert Woolson who served in the Union Army as a drummer boy. There were three men who claimed to be Confederate veterans who lived longer than Woolson; however, one of those has been completely debunked and no confirmation of service of the other two has ever been found.

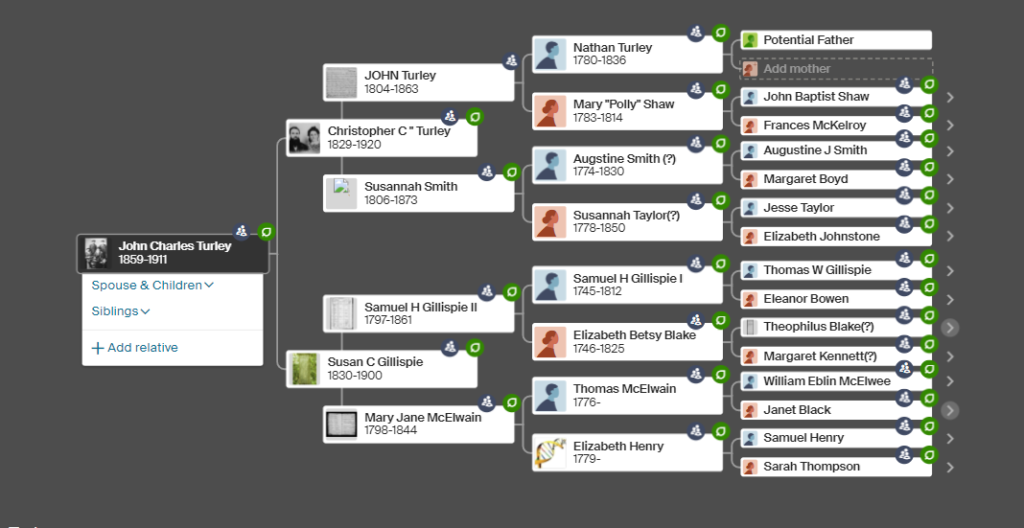

Hamilton And Lincoln Still Have Something To Tell US

By John Turley

On September 26, 2023

In Commentary, History

Objections and Answers respecting the Administration

of the Government

Alexander Hamilton 18 August 1792

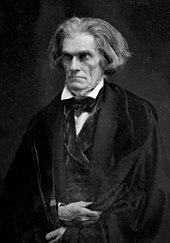

“The truth unquestionably is, that the only path to a subversion of the republican system of the Country is, by flattering the prejudices of the people, and exciting their jealousies and apprehensions, to throw affairs into confusion, and bring on civil commotion…

When a man unprincipled in private life, desperate in his fortune, bold in his temper, possessed of considerable talents, having the advantage of military habits—despotic in his ordinary demeanour—known to have scoffed in private at the principles of liberty—when such a man is seen to mount the hobby horse of popularity—to join in the cry of danger to liberty—to take every opportunity of embarrassing the General Government & bringing it under suspicion—to flatter and fall in with all the non sense of the zealots of the day—It may justly be suspected that his object is to throw things into confusion that he may “ride the storm and direct the whirlwind.””

Speech to the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield

Abraham Lincoln 1838

Is it unreasonable then to expect, that some man possessed of the loftiest genius, coupled with ambition sufficient to push it to its utmost stretch, will at some time, spring up among us? And when such a one does, it will require the people to be united with each other, attached to the government and laws, and generally intelligent, to successfully frustrate his designs….

Distinction will be his paramount object, and although he would as willingly, perhaps more so, acquire it by doing good as harm; yet, that opportunity being past, and nothing left to be done in the way of building up, he would set boldly to the task of pulling down….

I first came across these quotations in an article by Jeffery Rosen published in the Wall Street Journal. The Grumpy Doc does not need to add anything further to them and will leave them for your thought and consideration.