The Decline of Community Newspapers

“Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” Thomas Jefferson’s words resonate now more than ever in today’s media landscape, where local newspapers—the cornerstone of informed citizenship—are vanishing at an alarming rate. But it is more than just newspapers at risk—it is our very democracy.

Growing up in Charleston during the 1950s and 60s, I witnessed firsthand how integral newspapers were to community life. From delivering The Gazette as a boy to relying on its pages for news of local events and government, newspapers were our primary connection to the world around us.

There weren’t a lot of options for news then. There were no 24-hour news channels. National news on the three networks was about 30 minutes an evening and local news was about 15 minutes. By the late 1960s national news had increased to 60 minutes and most local news to about 30 minutes. Given the limitations of time on the local stations, most of the broadcast was taken up with weather, sports, and human-interest stories with little time left to expand on hard news stories.

We depended on our newspapers for news of our cities, counties, and states and the papers delivered the news we needed. Almost everyone subscribed to and read the local papers. They kept us informed about our local politicians and government and provided local insight on national events. They were also our source for information about births, deaths, marriages, high school graduations and everything we wanted to know about our community.

While newspapers were central in the mid-20th century, the proliferation of digital and broadcast media in the 21st century has transformed how we consume news. There are 24-hour news networks, but they often are a case of too much time and too little news. There are the social media—X (Twitter), Facebook, Tik Tok, Instagram, Truth Social and many other online entities that claim to provide news.

Even though local television news has expanded its format and increased coverage of local hard news, it remains heavily weighted toward sports, weather, and human interest. It is somewhat akin to reading the headline and the first paragraph in a newspaper story. It doesn’t provide in-depth coverage, but hopefully, it motivates people to find out more about events that concern them.

Still, it’s the local newspapers that provide detailed news about local and state events. Here in Charleston our newspapers were consolidated into a single daily paper several years ago. Despite reduced staffing and subscribership, they still make a valiant effort to cover our local news. Eric Eyre provided Pulitzer Prize winning coverage of the opioid epidemic. Currently Phil Kabler, though officially retired, continues to provide insight into the legislature and state government. Mike Tony, another reporter deeply involved in the community, provides coverage of West Virginia energy issues and the ongoing business foibles of our former governor and now senator. Mike recently informed us of an inappropriate—possibly illegal—grant made by the West Virginia Water Development Authority to a private Catholic College in Ohio. The college espouses multiple far right conservative political positions, although they claim this will not influence their project in West Virginia. Mike also pointed out the state statutory requirements for the grant were not met and that the governor’s office, as usual, had no comment. All this was done while West Virginia communities that have been without safe drinking water for months did not receive grants or any other assistance to improve their water systems.

Will TV news ever be able to provide the details about our community? The format of the newspaper allows for more detailed presentations and for a larger variety of stories. The reader can pick which stories to read, when to read them and how much of each to read. I don’t believe that broadcast news will ever fill the role of a free press. The broadcast is an ethereal thing. You hear it and it’s gone. It is always possible to record it and play it back, but most people don’t. Newspapers by their very nature encourage critical thinking. You can read it, think about it, and read it again. There are times when on my second or third reading of an editorial or a news article I’ve changed my opinion about either the subject or the writer. A news broadcast doesn’t lend itself to this type of reflection. When listening to broadcast news I often find my mind wandering as something that the broadcaster said sends me in a different direction.

I worry about the future of newspapers. According to a study by Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, more than 360 newspapers have closed nationally since the beginning of the COVID pandemic. Since 2005 over 3300 newspapers have closed or consolidated—more than one third of the nation’s total. The U.S. has also lost about 43,000 newspaper journalists, representing nearly two-thirds of the total. It would be a tragedy to continue losing newspapers and journalists at this rate.

I beg everyone to please subscribe to your local newspapers. I generally prefer the hands-on, physical newspaper though I understand many people prefer the convenience of the digital version and I find myself moving in this direction. Whichever version you prefer, please subscribe. Don’t pretend that online sources, such as Facebook, X, and Instagram will provide you with local news rather than just gossip. Even the online news feeds from the dedicated news networks such as CNN or Fox provide little more than headlines. There’s little you can use to make an informed decision.

Without local news, we risk losing touch with how local and state governments affect our lives. Without this knowledge, we may be at risk of losing our freedom. Many countries that have succumbed to dictatorship have first lost their free press. One of the first acts of the would-be dictator is to attempt to silence the free press.

In my opinion, broadcast news is controlled by advertising dollars and viewer ratings affecting their coverage and orientation. News seems to be treated like any entertainment program with the output designed to attract an audience, not present facts. I recognize that this can be the case with newspapers as well, but it seems to me that it’s much easier to detect bias in the written word than in the spoken word. Too often we can get caught up in the emotions of the presenter or in the graphics that accompany the story.

With that in mind, I recommend that if you want unbiased journalism, please support your local newspapers before we lose them. Once they are gone, we will never get them back and we will all be much the poorer as a result.

I will leave you with a final quote.

A free press is the unsleeping guardian of every other right that free men prize; it is the most dangerous foe of tyranny. –Winston Churchill

Choosing Not to Know

By John Turley

On March 19, 2025

In Commentary

Why We Avoid Truths That Make Us Uncomfortable

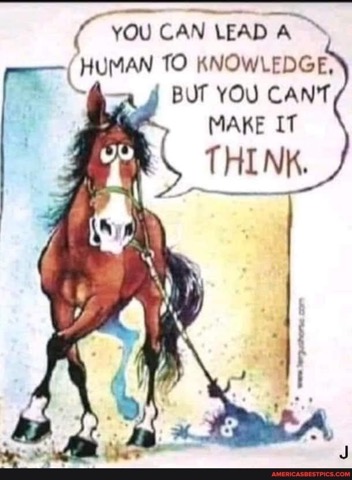

One afternoon during the COVID lockdown I was scrolling through online news sites looking for something to read. I realized I was intentionally bypassing sites I knew I would disagree with. This surprised me because I have always been a proponent of critical thinking. Here I was practicing its antithesis— willful ignorance—intentionally avoiding evidence that contradicts my beliefs or preferences.

This behavior may seem irrational, yet it persists across all aspects of life, from personal relationships to religious beliefs to political ideologies. Understanding why we cling to falsehoods, what value we derive from this behavior, and how we can counter it is essential for fostering open-mindedness and informed decision-making.

We often assume that willful ignorance is something that affects “them”—the people with whom we disagree. Anyone can fall victim to willful ignorance, even you and me.

When we encounter evidence that contradicts our beliefs, we experience cognitive dissonance—a state of mental discomfort caused by holding two conflicting ideas simultaneously. To resolve this discomfort, we often reject new evidence rather than altering our existing worldview.

We tend to seek out and interpret information in ways that confirm our pre-existing beliefs while ignoring or dismissing evidence to the contrary. This conformation bias reinforces our opinions and shields us from uncomfortable truths.

Our beliefs are often tied to our social identity. Having our beliefs challenged can feel like an attack on our sense of self or on our group affiliations. Maintaining allegiance to a shared belief—whether religious, political, or cultural—can feel more important than factual accuracy.

Contradictory evidence can create fear and uncertainty, especially if it undermines our understanding of the world. Clinging to familiar falsehoods can provide us a sense of security and predictability.

We invest time, energy, and emotions into our beliefs. Admitting we were wrong may feel like a personal failure or a waste of effort, making it easier to reject new information than to reconsider long-held positions.

Despite its drawbacks, willful ignorance offers psychological and social benefits that make it appealing. Ignoring uncomfortable truths can protect us against guilt, shame, or fear, while providing a sense of inner peace and emotional comfort. We may attempt to maintain our sense of self and group identification by avoiding information that threatens our worldview. Engaging with complex or contradictory information requires mental effort. Ignoring it simplifies decision-making, reducing cognitive load. Aligning with a group’s shared beliefs—regardless of their accuracy—fosters social cohesion and acceptance.

While anyone can fall into willful ignorance, certain factors may make some groups more prone to it. Studies show that individuals across the political spectrum exhibit willful ignorance, though the issues they ignore vary. For example, conservatives may deny climate change, while progressives may overlook the economic costs of policies they favor. Groups that emphasize doctrinal adherence may be more resistant to evidence that challenges theological teachings. Older adults may resist evidence that challenges long-held beliefs. However, younger individuals can also exhibit willful ignorance, particularly in social media echo chambers.

We are more likely to reconsider our beliefs in an environment where we feel we have been heard and understood rather than attacked and ridiculed. Constructive dialogue, rather than confrontation, opens the door to change. Facts alone often fail to persuade. Framing evidence within emotionally resonant stories can make it more effective. Presenting new information in small, digestible portions helps reduce cognitive dissonance and makes new ideas less threatening. We are more likely to accept information from sources we trust, particularly those who share our cultural or ideological background.

Convincing someone that their beliefs are counterproductive requires tact and patience. But, before trying to change others, we must first examine our own beliefs to ensure we are not guilty of the same behavior. Self-examination is the first step in addressing willful ignorance.

Willful ignorance thrives in environments of fear, division, and mistrust. Countering it requires empathy, compassion, and truth. If we engage with others in a spirit of understanding rather than confrontation, we have a better chance of bridging divides and creating meaningful change.

The journey is challenging, but the rewards—for both individuals and society—will be worth the effort.